Hey there, friend. If you’ve ever stared at a chart of baby‑death numbers and felt a mix of hope and worry, you’re not alone. The newest infant mortality study shows an encouraging downward trend in overall deaths, but it also flags a troubling rise in sudden‑unexpected infant deaths (SUID). In the next few minutes, let’s unpack what those numbers really mean, why they matter to you, and what we can all do to keep every newborn safe.

Current U.S. Landscape

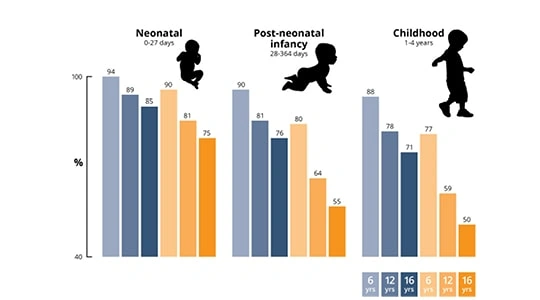

First off, the hard facts. According to the CDC’s 2023 MMWR report, the national infant‑mortality rate (IMR) is now about 3.58 deaths per 1,000 live births for the neonatal period—a modest 3 % uptick from the previous year. Post‑neonatal rates have crept up about 4 % as well. Those percentages may look small, but each bump translates to dozens of families grappling with sudden loss.

What’s driving the disparity? A quick look at the data reveals three recurring themes:

- Infections: Still the top cause, especially in low‑resource or rural settings.

- Birth injury & asphyxia: Frequently linked to limited access to skilled birth attendants.

- Prematurity: A challenge that can cascade into many complications.

Geographically, the story isn’t uniform. Rural counties across the Midwest and South report higher SUID rates, while many urban centers have seen sharper declines. Racial and ethnic gaps persist too—infants of Black and Hispanic mothers still face mortality rates two to three times higher than their white peers (a study from 2023 highlights this). These patterns matter because they point to where our interventions should focus next.

Historical Mortality Roots

Understanding why we’re here today starts with a quick trip back in time. In the late 19th century, infant mortality in the United States hovered between 15 % and 30 %—meaning up to three out of ten babies never survived their first year. Utah’s historical records, for instance, show this grim reality between 1850 and 1939 (Infant Deaths in Utah).

What turned the tide? A cascade of early 20th century medicine breakthroughs—clean water, vaccination, antiseptic surgery, and the rise of public‑health laboratories—dramatically lowered infections. At the same time, the expansion of medical schools (thanks to the Flexner Report) produced a new generation of physicians trained in obstetrics and pediatrics.

Even before modern hospitals, communities began to notice that cleaner homes and better nutrition saved lives. Those humble public‑health reforms laid the groundwork for the steep mortality decline we see in the mid‑20th century charts.

Modern Risk Drivers

Fast‑forward to today. While we’ve solved many old problems, new ones have emerged. The latest infant mortality study points to a few key drivers behind the SUID rise:

- Sleep environment: Unsafe bedding, soft mattresses, and prone sleeping remain the leading modifiable risks for SIDS.

- Socio‑economic stressors: Families living in poverty often face overcrowded housing, limited access to prenatal care, and higher smoking rates.

- Physician workforce gaps: Rural areas suffer from the physician decline effects, meaning fewer OB‑GYNs and neonatologists are available to monitor high‑risk pregnancies.

- Medical‑school closures: When schools shut their doors, the pipeline of future specialists shrinks (medical school closures impact), deepening the shortage.

One eye‑opening case comes from northern Ghana, where a 7‑year study showed a neonatal mortality rate of 24 per 1,000 live births, with infections, birth injury, and prematurity accounting for most deaths (PLOS ONE). Though the setting is different, the underlying risks echo what we see in the U.S.—highlighting that clean‑birth practices and timely medical care are universal necessities.

Medical Workforce Impact

Let’s dig a little deeper into the human side of the equation. When a rural hospital loses its last OB‑GYN, expect a ripple effect: fewer prenatal visits, delayed C‑sections, and a higher chance that a newborn will be delivered without a specialist on hand. The public health reforms of the past taught us that a robust workforce is as important as clean water.

The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG, 2024) reports a 12 % drop in obstetric residency slots over the last decade, with many programs closing in underserved states. This shortage isn’t just a numbers game; it translates into longer travel times for expectant mothers and delayed emergency interventions—both of which can push an infant into the high‑risk SUID category.

What can be done? A few promising ideas are gaining traction:

- Loan‑repayment incentives: Offering tuition forgiveness to doctors who commit to practice in rural areas.

- Tele‑neonatology: Using video‑conferencing to bring specialist expertise into community hospitals.

- Midwife integration: Expanding licensing and training pathways for certified nurse‑midwives to fill gaps.

These solutions echo the spirit of past early 20th century medicine reforms—when communities rallied around local health initiatives and saw real, measurable drops in infant deaths.

Effective Public Interventions

History shows us that coordinated public‑health actions can move the needle dramatically. Some of the most successful interventions in the last century include:

| Intervention | Era | Impact on IMR |

|---|---|---|

| Clean‑water & sewage systems | Early 1900s | Reduced infection‑related deaths by ~30 % |

| Universal prenatal care programs | 1970s‑80s | Lowered prematurity rates by 15 % |

| Safe‑sleep education (AAP guidelines) | 1990s‑present | Cut SIDS rates in half in participating states |

| Home‑visiting nurse programs | 2000s‑present | Improved breastfeeding rates, reduced SUID by ~12 % |

Today, we can build on that legacy. The public health reforms that emphasized vaccination, sanitation, and education are being adapted for the 21st century: mobile health clinics, culturally tailored safe‑sleep kits for low‑income families, and community health worker outreach in underserved neighborhoods.

On a personal level, you can become an advocate by sharing these simple safe‑sleep steps with friends and family:

- Always place babies on their backs.

- Use a firm mattress with a fitted sheet—no blankets or pillows.

- Keep the sleep area in the same room as you, but not the same bed.

- Offer a pacifier after feeding, unless the baby refuses it.

- Avoid exposure to smoke, even second‑hand.

These actions might seem tiny, but collectively they save lives—just as clean water did a century ago.

Using Data Wisely

Now that you’ve seen the big picture, you might wonder how to make sense of raw numbers yourself. Here are a few tips for the curious reader:

- Start with trusted sources: CDC WONDER, National Vital Statistics System, and linked birth‑infant‑death files are gold‑standard datasets.

- Watch out for pitfalls: Don’t confuse raw counts with rates, and always adjust for population size, race, and geography.

- Visualize trends: A simple line chart of IMR over the last decade can reveal whether a recent uptick is a blip or a new pattern.

- Break it down: Look at sub‑categories—neonatal vs. post‑neonatal, urban vs. rural, or by maternal age.

- Use tools you already have: Excel’s “Insert > Chart” feature lets you create a clean graph in minutes. Plot the CDC numbers, add a trendline, and you’ve got a visual story to share at your next community meeting.

When you pair solid data with the human stories behind them, the result is both compelling and actionable. That’s the spirit of the infant mortality study: numbers are important, but the families they represent are the heart of the issue.

Wrapping It All Up

We’ve traveled from 19th‑century birth registers to today’s high‑tech data dashboards, seeing both triumphs and new challenges along the way. The good news? Overall infant mortality continues its long‑term decline, a testament to decades of public‑health reforms and medical progress. The not‑so‑good news? Sudden‑unexpected infant deaths are nudging the numbers back up, especially in communities hit hardest by socioeconomic stress and physician shortages.

What can you do right now? Start a conversation about safe sleep, support local clinics that recruit physicians to rural areas, and keep an eye on the latest research—because every piece of knowledge helps us protect the tiniest members of our society.

Feel free to explore more on related topics:

- medical school closures impact

- public health reforms

- physician decline effects

- early 20th century medicine

We’re all in this together—let’s keep learning, sharing, and caring for the newest generation. After all, every baby deserves a safe, healthy start.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.