Imagine your immune system as an elite squad of detectives, each trained to spot a specific villain. Monoclonal antibodies (or mAbs) are like bespoke detectives that scientists hand‑craft in the lab—identical copies that hunt down one particular target, whether it’s a rogue cancer cell, an over‑active immune protein, or a sneaky virus.

Why should you care? Because these engineered proteins are the backbone of many of the most precise treatments available today. Knowing how they work, what they can do for you, and the possible downsides can turn a vague “I’ve heard of mAbs” into a confident conversation with your doctor.

What Are Monoclonal Antibodies

Simple definition

In plain English, a monoclonal antibody is a lab‑made protein that mimics the natural antibodies your body produces. While natural antibodies are a mixed crowd, each with its own target, monoclonal antibodies are a single‑file line—every molecule is identical and binds to the exact same part of a disease‑related protein.

How they’re made

Early versions came from hybridoma cells—fusion of a mouse immune cell with a cancer cell that could grow forever. Modern Cleveland Clinic explains that today most mAbs are produced using recombinant DNA technology. Scientists insert the gene for the desired antibody into mammalian cells (often CHO cells), let the cells churn out the protein, then purify and test it. This method yields huge, consistent batches that meet strict quality standards.

Key formats

Not all antibody drugs look the same. Here are the most common flavors:

| Format | What it means | Typical use |

|---|---|---|

| Full‑length IgG | Classic Y‑shaped antibody, long half‑life | Most oncology & autoimmune mAbs |

| Fragment (Fab, scFv) | Smaller, penetrates tissue better | Eye drops, imaging agents |

| Bispecific | Two different binding sites in one molecule | Brings immune cells to cancer cells (e.g., blinatumomab) |

| Antibody‑drug conjugate (ADC) | Antibody linked to a toxin or radioisotope | Targeted cancer killing |

How They Work

Lock‑and‑key binding

Think of a monoclonal antibody as a key that fits a single lock—a specific antigen on a cell’s surface. When the key turns, it can either block the lock (preventing the cell from sending growth signals) or flag the cell for destruction by the immune system.

Mechanisms of action

Direct cell killing

Some mAbs bind to a tumor antigen and trigger antibody‑dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). In plain speak, they wave a red flag that tells natural killer cells, “Hey, eat this!”

Immune‑checkpoint inhibition

Drugs like pembrolizumab (Keytruda) block proteins such as PD‑1 that normally keep the immune system in check. By releasing the brakes, the body can recognize and attack cancer cells more aggressively. Mayo Clinic notes that this approach has transformed treatment for melanoma and lung cancer.

Delivery of toxins

ADCs fuse the targeting precision of an antibody with the lethal punch of a chemotherapy drug. The antibody delivers the toxin straight to the cancer cell, sparing most healthy tissue.

Real‑world example

Trastuzumab (Herceptin) homes in on the HER2 protein, overexpressed in about 20 % of breast cancers. By binding HER2, it both blocks growth signals and recruits immune cells. The result? A dramatic increase in survival for HER2‑positive patients.

Therapeutic Areas

Oncology

mAbs dominate modern cancer care. FDA‑approved examples include:

- Herceptin – HER2‑positive breast & gastric cancers

- Keytruda – melanoma, non‑small cell lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma

- Opdivo – renal cell carcinoma, melanoma

- Rituxan – non‑Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia

These drugs have shown response rates ranging from 30 % to 70 % in appropriate patient groups, often extending progression‑free survival by months or even years.

Autoimmune & Inflammatory

When the immune system goes rogue, monoclonal antibodies can dial it back. Adalimumab (Humira) blocks tumor necrosis factor‑α, easing rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and psoriasis. Rituximab depletes B‑cells, helping treat multiple sclerosis and vasculitis. The precision of these “biologic therapies” means fewer systemic side‑effects compared with traditional steroids.

Infectious diseases

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, mAbs such as bamlanivimab and sotrovimab were deployed to neutralize the virus early in high‑risk patients. According to the NCBI Bookshelf, early treatment reduced hospitalizations by up to 70 %.

Newer antibody cocktails are also being tested for RSV and influenza, promising seasonal protection for vulnerable groups.

Transplant & Rare Disorders

Anti‑CD20 antibodies (e.g., rituximab) are used to prevent organ rejection, while rare‑disease programs employ bespoke mAbs to replace missing proteins or neutralize harmful autoantibodies.

Benefits & Why Choose

Precision reduces collateral damage

Because monoclonal antibodies are designed to hit only one target, they often spare healthy cells. The Cleveland Clinic notes that this precision can “improve effectiveness and reduce some side effects.”

Scalable production

Large‑batch consistency means every patient receives a drug that looks and works the same, lowering variability and simplifying dosing.

Convenient administration

Many mAbs are given as outpatient infusions lasting 30 minutes to two hours, and a growing number are approved for sub‑cutaneous injection—sometimes even self‑administered at home.

Combination possibilities

Because they act through a different mechanism, mAbs can be paired with chemotherapy, radiation, or other biologics for a synergistic effect.

Patient story

Jane, a 58‑year‑old with HER2‑positive breast cancer, describes her experience: “I was nervous about another IV, but the infusion was quick, and I felt like I was taking an active step. After a year, my scans were clear—something I never thought possible before mAb therapy.”

Risks & Side Effects

Infusion reactions

During or shortly after the infusion, you might notice fever, chills, rash, or shortness of breath. These are usually mild and can be managed by slowing the drip or giving antihistamines.

Serious immune events

- Anaphylaxis: A rare but life‑threatening allergic reaction.

- Cytokine‑release syndrome (CRS): Also called a “cytokine storm,” it can cause fever, low blood pressure, and organ stress.

- Serum sickness: A delayed reaction where the immune system attacks the infused antibody itself.

Condition‑specific risks

In fast‑growing lymphomas, rapid tumor death can overwhelm kidneys—a phenomenon called tumor‑lysis syndrome. Certain mAbs used for blood‑cancers have been linked to acute kidney injury, so labs are closely monitored.

Managing the risks

Doctors usually perform baseline labs, pre‑medicate with acetaminophen and steroids, and watch vitals during the first infusion. If a reaction occurs, they can pause the drip, give meds, and resume once stable.

Treatment Journey

Pre‑treatment work‑up

Before the first dose, you’ll likely undergo:

- Blood tests to check liver, kidney, and immune status.

- Imaging (CT, MRI) to locate disease.

- Biomarker testing – for example, HER2 testing in breast cancer or PD‑L1 expression in lung cancer.

Administration routes

Intravenous infusion

Most mAbs are given through a peripheral line. The first infusion can last up to two hours; subsequent doses often shorten as tolerance builds.

Sub‑cutaneous injection

Some newer formulations (e.g., adalimumab) can be injected under the skin, allowing patients to self‑administer at home after proper training.

Follow‑up and monitoring

Typical schedules involve an infusion every two to three weeks, with periodic blood work to watch for liver enzymes, blood counts, and any emerging antibodies against the drug itself.

Cost considerations

Monoclonal antibodies are pricey, but biosimilars—essentially “generic” versions—have entered the market, bringing costs down by 20‑30 %. Insurance plans often cover the original or the biosimilar; a pharmacy specialist can help you navigate copays and prior authorizations.

Future Outlook

Next‑generation formats

Scientists are engineering triple‑specific antibodies that can bind three targets at once, as well as oral‑bioavailable antibody fragments that survive the digestive tract. These innovations could make treatment even more convenient.

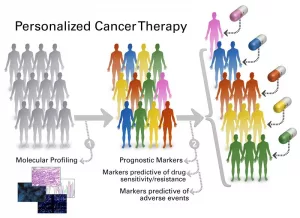

Personalized antibody cocktails

Imagine a lab test that tells you exactly which antigens your tumor expresses, then automatically creates a bespoke cocktail of mAbs just for you. Early trials are already showing promise.

Global pipeline

The WHO reports over 400 monoclonal antibodies in clinical development worldwide, spanning oncology, infectious disease, neurology, and rare genetic disorders. The pace of approval suggests that in the next decade, many diseases we now label “hard‑to‑treat” may have a targeted antibody option.

Conclusion

Monoclonal antibodies are a cornerstone of modern medicine—a class of biologic therapies that bring the precision of a detective’s magnifying glass to the battlefield of disease. They offer clear benefits: targeted action, often fewer side‑effects, and the flexibility to be combined with other treatments. At the same time, they carry risks—infusion reactions, rare immune storms, and condition‑specific complications—that require careful monitoring and open dialogue with your healthcare team.

Armed with this knowledge, you can ask the right questions, weigh the pros and cons, and feel confident about whether a monoclonal‑antibody therapy fits into your or a loved one’s treatment plan. If you’ve had personal experience with mAb therapy or have questions, share them in the comments below. Let’s keep the conversation going and help each other navigate this exciting, ever‑evolving field.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.