Did you know that the phrase “diabetes belly” isn’t a formal medical diagnosis, but a handy way doctors talk about extra fat hanging around your waist that can raise your chance of developing diabetes? In the next few minutes you’ll get the straight‑forward truth about what creates this belly, why it matters, and what you can actually do to shrink it – all without feeling like you’re reading a textbook.

What the Term Means

Definition – extra abdominal fat linked to diabetes

When people say “diabetes belly,” they’re usually pointing to the layer of visceral fat that sits deep inside the abdomen, right around your organs. This isn’t the soft‑spot you can pinch on the outside (that’s sub‑cutaneous fat); it’s the hidden, “hello‑I‑live‑inside‑you” kind of fat that releases chemicals making it harder for your body to use insulin properly.

Not a medical diagnosis

Even though the label sounds clinical, it’s really just a descriptive shorthand. You won’t find “diabetes belly” listed in any ICD‑10 code, but you will see it appear in nutrition blogs, diabetes education handouts, and forums where people swap real‑world experiences.

Visceral vs. sub‑cutaneous fat

Visceral fat hangs out around the liver, pancreas, and intestines, while sub‑cutaneous fat lives just under the skin. Visceral fat is far more metabolically active – it talks to your hormones, your immune system, and your brain, stirring up inflammation that can sabotage insulin. A quick graphic in your mind: think of visceral fat as the mischievous “inner‑city” neighbor, and sub‑cutaneous fat as the quiet “suburb” neighbor.

Quick comparison

| Feature | Visceral (diabetes belly) | Sub‑cutaneous |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Deep, around organs | Just under skin |

| Metabolic activity | High – releases inflammatory proteins | Low – mainly storage |

| Health impact | Insulin resistance, heart disease | Cosmetic concerns |

Why It Increases Risk

Inflammatory proteins and insulin resistance

Visceral fat releases molecules like retinol‑binding protein 4 (RBP‑4) and various cytokines. According to a 2024 study in research published in Diabetes Care, those proteins blunt insulin’s ability to usher glucose into your cells, leaving blood sugar levels higher than they should be.

Hormonal chaos

Chronic stress spikes cortisol, the “stress hormone.” Cortisol loves to hang out in the belly region, prompting extra fat storage there. A review on Healthline notes that sustained cortisol elevation is strongly linked to central obesity – the very thing we call diabetes belly.

Organ interference

When fat starts coating the liver and pancreas, it interferes with their normal functions. The liver becomes less efficient at regulating glucose, and the pancreas struggles to secrete the right amount of insulin. That double whammy nudges you closer to type 2 diabetes.

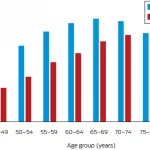

Statistical risk boost

People with a waist circumference above the thresholds listed below are about 2‑3 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those with slimmer waists. The numbers come from the latest WHO and Diabetes Australia data.

Waist‑circumference risk chart

| Group | Risk Threshold (cm) |

|---|---|

| Men – Caucasian | ≥ 102 cm |

| Women – Caucasian | ≥ 88 cm |

| Men – South Asian | ≥ 90 cm |

| Women – South Asian | ≥ 80 cm |

| Men – Maori/Pacific | ≥ 102 cm |

| Women – Maori/Pacific | ≥ 88 cm |

Common Causes

Caloric excess and sugar

Consuming more calories than you burn forces the body to stash the surplus. Diets high in simple sugars and refined carbs are especially guilty; they flood the bloodstream, push insulin levels up, and give visceral fat a green light to grow.

Sedentary lifestyle

Hours glued to a desk, endless scrolling, or binge‑watching TV all mean fewer calories burned. Even if you’re not gaining weight visibly, the lack of movement lets belly fat slip in unnoticed.

Stress and cortisol

High‑pressure jobs, family worries, or not sleeping enough keep cortisol humming. Over time, cortisol tricks the body into holding onto abdominal fat as a protective reserve.

Genetics and ethnicity

Your DNA decides where your body prefers to store fat. Some ethnic groups, like South Asians, tend to accumulate visceral fat at lower waist sizes. That’s why a 90 cm waist for a South Asian man can be as risky as a 102 cm waist for a Caucasian man.

Hormonal changes

Menopause, thyroid disorders, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) all shift hormone balances, often tipping the scales toward more abdominal fat. Even a tiny thyroid slowdown can make your metabolism crawl.

Medication side‑effects

Certain antidepressants, antipsychotics, and steroids have a notorious reputation for adding inches around the middle. If you suspect a drug is the culprit, a chat with your doctor can uncover alternatives or strategies to counteract it.

How to Reduce Diabetes Belly

Nutrition strategies

- Protein & fiber first. A breakfast of Greek yogurt, berries, and a sprinkle of chia keeps blood sugar steady and curbs cravings.

- Trim fructose. Sugary drinks and processed snacks spike insulin, feeding visceral fat. A Diabetes Australia guide recommends swapping soda for sparkling water with a splash of lemon.

- Healthy fats matter. Omega‑3s from fish, walnuts, or flaxseed help improve insulin sensitivity.

- Mind the clock. Time‑restricted eating—eating all meals within an 8‑hour window—has shown promise in reducing belly fat without calorie counting.

7‑day sample menu

| Day | Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mon | Greek yogurt + berries | Quinoa salad + chickpeas | Grilled salmon + broccoli |

| Tue | Scrambled eggs + spinach | Turkey wrap (whole‑grain) | Stir‑fry tofu + mixed veg |

| Wed | Oatmeal + walnuts | Lentil soup + side salad | Baked chicken + sweet potato |

| Thu | Protein shake + almond milk | Grilled shrimp + quinoa | Veggie‑loaded chili |

| Fri | Avocado toast + poached egg | Greek salad + feta | Lean steak + asparagus |

| Sat | Fruit smoothie + chia | Veggie burger (lettuce bun) | Roasted cod + green beans |

| Sun | Whole‑grain pancakes + berries | Chicken Caesar (light dressing) | Vegetable lasagna (zucchini sheets) |

Exercise & physical activity

- Aerobic cardio. Aim for 150 minutes of moderate activity each week—think brisk walks, cycling, or dancing to your favorite playlist.

- Resistance training. Two to three sessions of weight‑lifting or body‑weight exercises (squats, push‑ups) build lean muscle, which burns more calories at rest.

- HIIT bursts. Short, intense intervals (20 seconds sprint, 40 seconds walk, repeat 8‑10 times) have been shown to slash visceral fat faster than steady‑state cardio alone.

Beginner 3‑Day Workout

| Day | Routine |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | 30‑min brisk walk + 3 × 12 squats, lunges, planks (30 sec each) |

| Day 2 | HIIT – 20 sec jump‑jacks, 40 sec rest – repeat 8 times |

| Day 3 | 30‑min cycling + 3 × 10 push‑ups, dumbbell rows, side‑plank (30 sec each) |

Lifestyle & stress management

- Sleep well. Seven to nine hours of quality sleep helps keep cortisol in check and supports hormone balance.

- Stress‑busting habits. Simple practices—deep breathing, a 10‑minute walk, or a favorite hobby—lower cortisol, making it harder for belly fat to cling on.

- Alcohol & smoking. Both elevate visceral fat storage. Cutting back, or quitting altogether, can yield noticeable waist‑line improvements within weeks.

Medical & professional help

Measuring your waist is the first concrete step. If the numbers in the risk chart above look alarming, consider booking a quick appointment with a dietitian or an endocrinologist. They can tailor a plan, check if any of your meds are contributing, and monitor progress with lab tests.

Real‑World Stories

Case 1: Office‑worker transformation

Mark, 45, spent most of his day sitting at a desk and eating take‑out. After a routine check‑up revealed a waist of 108 cm, he started a simple program: swapping sugary soda for water, walking 30 minutes after lunch, and doing the 3‑day workout outlined above. In 12 weeks his waist dropped to 98 cm, his fasting glucose fell from 112 mg/dL to 99 mg/dL, and his doctor noted “significant reduction in visceral fat” on the latest scan.

Case 2: Post‑menopausal improvement

Susan, 58, noticed her belly expanding despite no major weight gain. Genetic testing showed a predisposition to central obesity. She partnered with a certified dietitian, embraced a Mediterranean‑style diet rich in olive oil, fish, and leafy greens, and added two strength‑training sessions per week. After eight months, her waist shrank from 92 cm to 84 cm, and her HbA1c dropped from 6.2% to 5.5%, moving her out of pre‑diabetes range.

Key Takeaways

Understanding “diabetes belly” helps you see that the extra tummy isn’t just a cosmetic concern—it’s a warning sign that your body’s insulin system is under pressure. The good news? You control the levers. By eating smarter, moving more, sleeping better, and managing stress, you can shrink visceral fat, improve insulin sensitivity, and lower the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Take the first step today: measure your waist, jot down a quick food log, and commit to a 10‑minute walk tomorrow morning. Small actions add up, and before you know it, you’ll be waving goodbye to that “diabetes belly” and hello to a healthier, more energetic you.

If you have questions, ideas, or a story of your own, drop a comment below. Let’s tackle this together—because every inch you lose is a win for your whole body.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.