Imagine you’ve been dealing with heartburn for years, and then a doctor drops the phrase “Barrett’s esophagus” on the exam table. Your brain immediately flips to “cancer?” and “what now?” — a perfectly natural reaction. The good news is that, while Barrett’s esophagus does raise the odds of a specific kind of esophageal cancer, it isn’t a death sentence. With the right knowledge, the right checks, and a few lifestyle tweaks, you can keep the risk low and feel in control of your health again.

In this article we’ll break down exactly what Barrett’s esophagus is, who tends to get it, why regular esophageal cancer screening matters, and the newest, less‑invasive ways to keep an eye on your esophagus without spending the night in a hospital. Let’s chat like friends over a cup of coffee—no jargon, just clear, caring information you can actually use.

What Is Barrett’s?

Definition & Simple Pathology

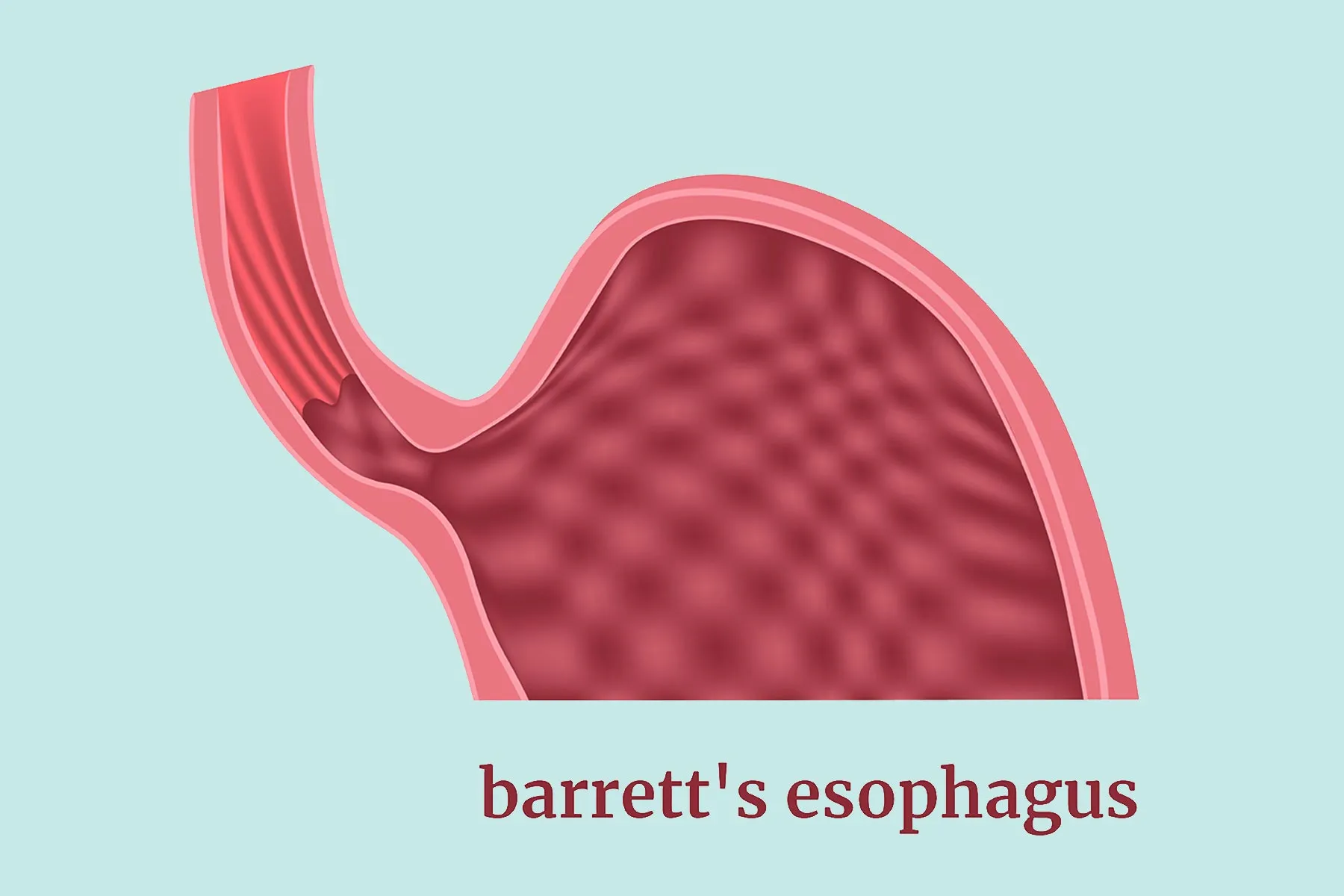

Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the lining (the mucosa) of the lower esophagus. Normally that lining is made of flat, pink squamous cells that protect the tube from food. Over time, chronic acid reflux can cause those cells to transform into columnar cells that look more like the intestine. This “metaplasia” is the body’s way of protecting itself, but it carries a slightly higher risk for turning cancerous.

How GERD Triggers the Change

When the lower esophageal sphincter (the valve between your esophagus and stomach) doesn’t close tightly, stomach acid splashes back up—what doctors call gastro‑esophageal reflux disease (GERD). According to MedlinePlus, that repeated acid exposure can erode the normal squamous cells, prompting them to become the more resilient columnar type.

Visual Aid Idea

Imagine a painted fence (the normal lining) that gets constantly splashed with paint (acid). Over time, you replace the splattered boards with a water‑resistant material (columnar cells). The new fence looks different—but it’s still standing.

Who Is At Risk?

Demographic Factors

Age over 55, being male, and having a Caucasian background tip the odds upward. Obesity and smoking add extra weight to the risk scale. If you check any of those boxes, it doesn’t mean you’ll definitely develop Barrett’s, but it does mean you should stay a little more vigilant.

Clinical Risk Factors

Long‑standing GERD (usually more than five years), a hiatal hernia, or a family history of Barrett’s or esophageal cancer also raise the likelihood. Even if you’re not feeling any heartburn, a silent GERD can still be at work behind the scenes.

Lifestyle Contributors

Heavy alcohol use, caffeine, chocolate, and mint can all relax the lower sphincter, making reflux more frequent. A simple habit change—like swapping late‑night pizza for a lighter meal—can make a noticeable difference.

| Risk Factor | Typical Impact | How to Mitigate |

|---|---|---|

| Age > 55 | Higher baseline risk | Regular surveillance endoscopies |

| Male gender | 2‑3× risk vs. women | Stay active, maintain healthy weight |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | Increases reflux pressure | Balanced diet + daily walk |

| Smoking | Damages esophageal cells | Quit—nicotine patches help |

| Long‑term GERD | Direct cause of metaplasia | PPIs or H2 blockers, lifestyle tweaks |

Why Screening Matters

From Barrett’s to Cancer

Barrett’s itself isn’t cancer, but it does raise the odds of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma—roughly a 0.5 % chance per year. While that sounds scary, it’s still a low absolute risk, especially when caught early. Regular esophageal cancer screening can spot precancerous changes (dysplasia) before they turn into a tumor.

Recommended Surveillance Schedule

Guidelines from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggest an endoscopic check every 3‑5 years for non‑dysplastic Barrett’s. If low‑grade dysplasia shows up, the interval shortens to every 6‑12 months, and higher‑grade dysplasia may prompt immediate treatment.

What “screening” Really Means

Screening isn’t a one‑time test; it’s a partnership. It’s you, your doctor, and the tools you both trust to keep an eye on the lining. Think of it like changing the oil in your car—you wouldn’t wait for the engine to seize before going to the garage.

Screening Options Today

Pill‑on‑a‑Thread Test

The pill‑on‑a‑thread test is a capsule you swallow that contains a tiny, absorbent thread. As it moves through the esophagus, the thread collects cells that are later examined under a microscope. No sedation, no scopes—just a quick office visit.

Capsule Sponge Test

Similar in spirit, the capsule sponge test involves a small capsule attached to a string. You swallow the capsule, it expands into a soft sponge once it reaches the stomach, and then you pull it back up, bringing with it a sample of esophageal cells. It’s painless and can be repeated annually if needed.

Standard Endoscopy

Traditional upper‑GI endoscopy remains the gold standard because it lets the doctor see the esophagus directly and take targeted biopsies. It’s more invasive—often requiring mild sedation—and can be a bit uncomfortable, but it provides the most detailed view.

Endoscopy Alternative Overview

If you’re looking for an endoscopy alternative that balances accuracy and comfort, the pill‑on‑a‑thread and capsule sponge are leading the pack. They’re part of a movement toward less‑invasive screening, giving patients more options without sacrificing safety.

| Test | Invasiveness | Typical Frequency | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Endoscopy | High (sedation) | Every 3‑5 yr (or sooner) | Direct visualization, targeted biopsies | Discomfort, cost, recovery time |

| Pill‑on‑a‑Thread | Low | Annual or as advised | No sedation, office‑based | May miss focal lesions |

| Capsule Sponge | Low | Yearly | Simple swallow, painless | Limited tissue depth |

| Imaging (barium, CT) | Minimal | Adjunct only | Non‑invasive | No histology, less sensitive |

Managing the Condition

Acid‑Control Medications

Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the front‑line heroes—they reduce stomach acid production and give the esophagus a chance to heal. Some people stay on a low dose indefinitely; others rotate to H2 blockers if symptoms are well‑controlled.

Diet & Self‑Care Tips

Think of your esophagus as a garden: it thrives when you water it gently and avoid harsh chemicals. Stay away from trigger foods like citrus, chocolate, peppermint, caffeine, and alcohol. Eat smaller meals, wait at least two‑hours after eating before lying down, and raise the head of your bed 6‑8 inches.

Endoscopic Therapies (When Dysplasia Appears)

If a biopsy shows dysplasia, physicians may offer radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). Both aim to destroy or remove the abnormal cells while preserving the rest of the esophagus. Success rates for preventing cancer are high—over 90 % in many studies.

Surgical Options

For severe reflux that can’t be tamed with medication, anti‑reflux surgery (like a Nissen fundoplication) re‑creates a tighter valve at the gastro‑esophageal junction. It doesn’t reverse Barrett’s, but it can stop further acid damage.

Talk To Your Doctor

Preparing for the Visit

Bring a list of all medications (including over‑the‑counter), note any new or worsening symptoms, and write down questions such as:

- “Based on my risk, how often should I be screened?”

- “Are there any less‑invasive tests that would work for me?”

- “What lifestyle changes would give me the biggest benefit?”

Discussing Less‑Invasive Options

Don’t be shy about asking for a pill‑on‑a‑thread test or a less‑invasive screening alternative if you’re hesitant about sedation. Many gastroenterology centers now offer these tools alongside traditional endoscopy.

Understanding the Risk‑Benefit Balance

Ask your physician to walk you through the numbers—how likely is dysplasia, what’s the chance of progression, and how each test weighs in terms of accuracy versus comfort. Shared decision‑making is the cornerstone of trustworthy care.

Conclusion

Barrett’s esophagus can feel like a heavy label, but with the right knowledge you can turn it into a manageable part of your health story. Recognize the risk factors, stay on top of esophageal cancer screening, and explore the newer endoscopy alternatives that let you keep a close watch without the hassle of full‑sedated procedures. Pair those medical steps with simple lifestyle tweaks, and you’ll give your esophagus the best chance to stay healthy.

Remember, you’re not alone on this journey. If you have questions, talk to your doctor, share your concerns with loved ones, and keep learning. Empowered decisions lead to better outcomes—so let’s stay curious, stay proactive, and keep that smile in your gut.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.