Hey there, friend. If you’ve ever wondered why some workers end up struggling to catch their breath even after they’ve left the job site, you’re not alone. The answer often comes down to something called silicosis – a lung disease caused by breathing in tiny particles of crystalline silica. In the next few minutes, I’ll walk you through exactly what silicosis causes, how it sneaks into our bodies, and what you can do to protect yourself or someone you care about. Grab a cup of tea, settle in, and let’s chat about this important (and surprisingly common) health topic.

What Triggers Silicosis

Silica isn’t a mysterious villain; it’s a mineral that makes up about 30% of the Earth’s crust. Think of quartz in sand, marble countertops, or the dust you see after a demolition project. When that rock is broken, cut, sand‑blasted, or ground, it releases respirable particles – usually smaller than 10 micrometers – that can travel deep into the lungs.

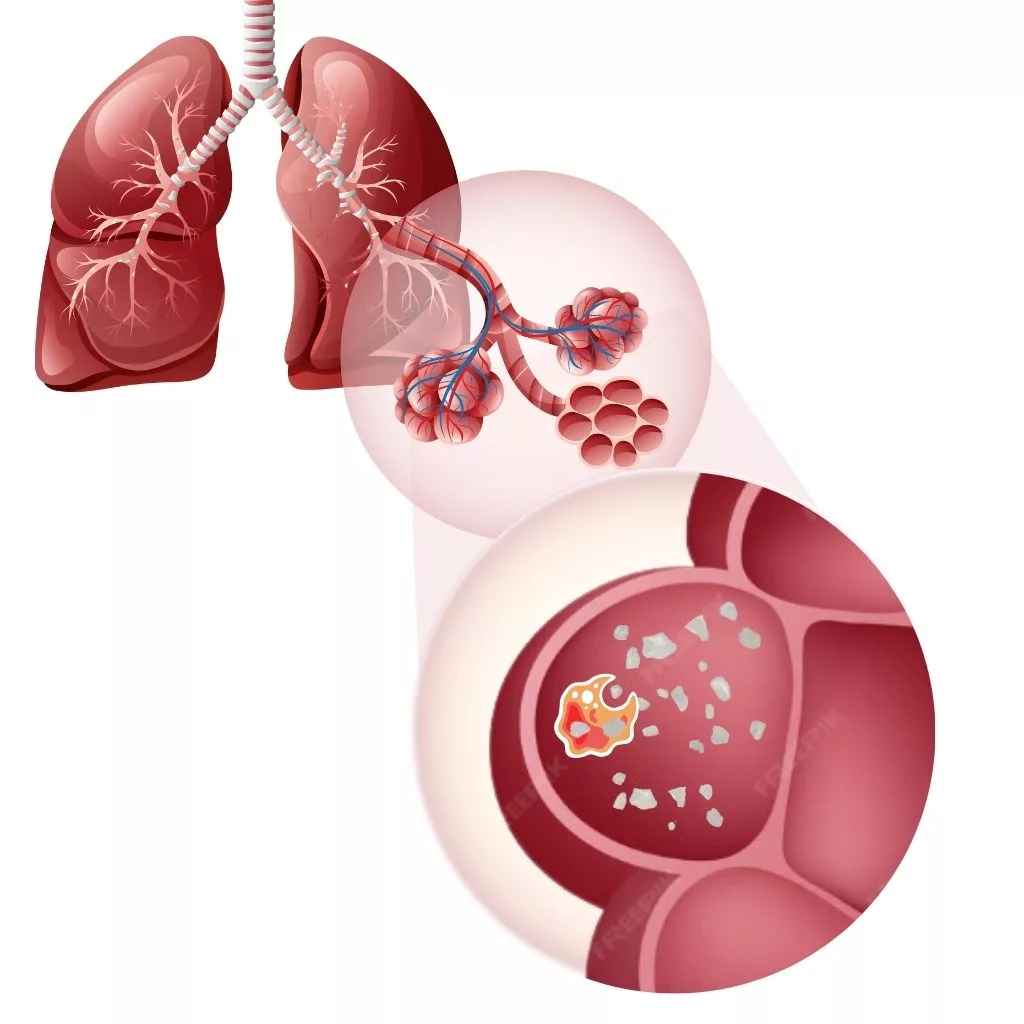

These fine bits are the real troublemakers. They lodge in the alveoli (the tiny air sacs where oxygen exchange happens) and set off an inflammatory cascade that eventually scars the lung tissue. Whether the exposure is steady and low‑level over ten years (the classic “chronic” route) or a short, intense burst of dust (think “acute” silicosis), the outcome can be the same: irreversible lung fibrosis.

How Dust Becomes Hazard

Not all dust is created equal. The danger hinges on three main factors:

- Particle size – Anything under 10 µm can slip past the nose and throat defenses.

- Silica content – Pure quartz or engineered stone can be upwards of 90% silica.

- Exposure duration – Hours, weeks, or years of breathing the dust.

When these pieces combine, macrophages – the immune cells that usually clean up debris – get overwhelmed. They try to engulf the silica crystals, but the sharp edges rupture their lysosomes, spilling toxic enzymes into surrounding tissue. This sparks a chain reaction called the macrophage pathways that fuels chronic inflammation and, eventually, scar formation.

According to a recent NIOSH study, workers exposed to dust concentrations above 0.05 mg/m³ for just a few years showed measurable declines in lung function – a stark reminder that “a little bit” can still be dangerous.

Pathway to Fibrosis

Here’s a quick, brain‑friendly rundown of what happens after those particles settle in the lungs:

- Inhalation – Crystalline silica particles enter the airways.

- Macrophage attack – Immune cells try to engulf the particles, leading to lysosomal rupture.

- Inflammasome activation – The NLRP3 inflammasome lights up, releasing cytokines like IL‑1β and TNF‑α.

- Fibroblast stimulation – These skin‑like cells start pumping out collagen, thickening the lung walls.

- Silicotic nodules – Visible on X‑rays as round “r‑type” opacities.

- Progressive Massive Fibrosis (PMF) – When nodules merge, the lung becomes stiff and breathing hard.

It’s interesting (and a bit eerie) that this same inflammasome pathway is involved in other crystal‑driven diseases, like gout and CPPD. Those conditions remind us that our bodies react similarly to very different “crystals” – whether they’re in a joint or a lung.

Types of Silicosis

| Type | Typical Exposure | Time to Onset | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic | Low‑level, ≥10 years | 10–30 years | Simple nodules, slow progression |

| Accelerated (Sub‑acute) | Higher concentration, 3–10 years | 5–10 years | Rapid nodule formation, quicker decline |

| Acute | Very high concentration, weeks‑months | <2 years | Diffuse inflammation, severe shortness of breath |

Understanding which type you (or a loved one) might be facing helps doctors decide how aggressively to monitor and treat the disease.

Who’s at Risk

Sound familiar? If you or someone you know works in any of the following, the odds are higher:

- Mining, quarrying, or stone‑cutting

- Construction demolition, sandblasting, or concrete drilling

- Engineered‑stone countertop fabrication

- Foundry work and metal‑casting

- Glass or pottery manufacturing

- Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) crews

Even hobbyists aren’t immune. A DIY enthusiast who sands a stone countertop at home without proper ventilation can create a mini‑silica storm in their garage. That’s why we often link silicosis to broader toxic particle diseases – the same principle applies to any inhaled fine particle.

Other risk amplifiers include smoking, pre‑existing lung conditions, and the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE). If you’ve ever wondered why two workers in the same shop can have very different health outcomes, these co‑factors often tip the scale.

Spotting Early Signs

Silicosis is notorious for being a “quiet” disease at first. The early symptoms can be so mild they’re easy to dismiss as a cold or seasonal allergies:

- Persistent dry cough

- Shortness of breath during exertion

- Occasional wheezing or chest tightness

As the disease advances, you might notice:

- Fatigue that won’t go away

- Weight loss despite a normal appetite

- Chest pain or a feeling of “tightness”

- Blue‑tinged lips (a sign of low oxygen)

- Swelling in the legs – a clue that the heart is working harder

If any of these sound familiar, especially if you have a silica‑exposed job history, see a healthcare provider sooner rather than later. Early detection gives you the best chance to slow progression.

Getting a Diagnosis

Diagnosing silicosis isn’t a single‑test affair. It’s a detective story that starts with a thorough occupational history – basically, a timeline of every job, the materials you handled, and the protective gear you used (or didn’t use). Your doctor will likely ask you to bring any old chest X‑rays or medical records to piece together the puzzle.

Imaging is key. A standard chest X‑ray can reveal the classic “r‑type” opacities, while a high‑resolution CT scan offers a detailed view of nodules and any progressive massive fibrosis. In a NIOSH bulletin, radiographic patterns were shown to correlate strongly with exposure intensity, giving clinicians a valuable clue.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) usually show a restrictive pattern – meaning the lungs can’t expand as fully as they should. You might see reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), indicating compromised gas exchange.

Because silicosis raises the risk of tuberculosis and other infections, doctors often order a TB skin test or IGRA, plus blood work to rule out autoimmune conditions that can mimic lung fibrosis.

Preventing Exposure

Here’s the good news: silicosis is largely preventable. If you’re in a high‑risk occupation, these steps can dramatically cut your odds of developing the disease.

Engineering Controls

- Wet methods – Using water to suppress dust during cutting or grinding.

- Local exhaust ventilation – Capture dust at the source with hoods and filters.

- Enclosed workstations – Seal off the process area whenever possible.

Administrative Controls

- Rotate workers to limit individual exposure time.

- Implement regular air‑sampling and maintain records.

- Provide training on safe work practices and proper PPE use.

Personal Protective Equipment

If you can’t eliminate the dust, wear a properly fitted N‑95 or higher‑rated respirator. Fit‑testing isn’t a one‑time event; it should be repeated at least annually.

Think of PPE as the last line of defense, much like a raincoat when a storm is already pouring. It won’t stop the rain, but it will keep you dry.

Managing the Disease

Unfortunately, once silicosis sets in, there’s no magic cure. However, we can still improve quality of life and slow the disease’s march.

- Quit smoking – If you smoke, stop now. It’s the single most effective step to preserve lung function.

- Vaccinations – Flu and pneumococcal vaccines reduce the risk of secondary infections.

- Medication – Corticosteroids may help during acute inflammation, but evidence is mixed. Some newer antifibrotic drugs (pirfenidone, nintedanib) are being explored for silicosis‑related fibrosis.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation – Exercise, breathing techniques, and counseling can boost stamina.

- Oxygen therapy – For those with low blood oxygen, supplemental O₂ can ease breathlessness.

- Lung transplant – In end‑stage disease, transplantation may be an option, though eligibility is strict.

Managing comorbidities is also crucial. Because silica exposure can trigger autoimmune reactions, staying vigilant for signs of inflammatory joint diseases is wise.

Bottom‑Line Checklist

- Know the jobs and tasks that generate silica dust.

- Measure airborne silica regularly; stay below OSHA’s 50 µg/m³ limit.

- Use wet cutting, local exhaust, or enclosed booths whenever possible.

- Fit‑test and wear a certified respirator if dust can’t be fully controlled.

- Get periodic health exams – chest X‑ray, PFTs, and symptom check‑ins.

- Quit smoking, stay vaccinated, and seek early treatment for any respiratory infection.

Conclusion

Silicosis may sound like a distant occupational hazard, but its roots are literally in the ground beneath our feet. By understanding silicosis causes, recognizing early warning signs, and championing robust safety measures, we can protect ourselves, our coworkers, and our families from this preventable lung disease. If you work with stone, sand, or any material that can turn into fine silica dust, take a moment today to evaluate your workplace controls – your lungs will thank you tomorrow.

Got a story of your own, or a question about dust safety? Feel free to reach out. We’re all in this together, and sharing knowledge is the best way to keep our air clean and our lungs healthy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.