If you or someone you love is living with cirrhosis, you’ve probably heard a lot of scary-sounding words—”transplant,” “resection,” “portal hypertension,” “MELD score.” It’s easy to feel overwhelmed, like you’re staring at a medical jargon jungle. The good news? You don’t have to navigate it alone, and the answers are often simpler than they appear. Below, I’ll walk you through the real basics of cirrhosis surgery—when it’s needed, what the options are, how doctors decide if you’re a good candidate, and what’s on the horizon. Think of this as a friendly coffee‑chat with a knowledgeable buddy who’s done the homework for you.

Who Needs Surgery

Clinical Triggers

Not every person with cirrhosis will face an operation. In most cases, doctors try medical therapy first, because surgery carries extra risk when the liver is already struggling. However, when the disease reaches certain “tipping points,” surgery becomes the safer—or the only—choice. Typical triggers include:

- Decompensated cirrhosis (Child‑B or Child‑C) with complications such as refractory ascites or variceal bleeding.

- MELD score ≥ 12, indicating a higher likelihood of postoperative liver failure.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that is ≤ 3 cm and meets transplant or resection criteria.

- Severe portal hypertension that threatens bleeding during an otherwise elective procedure.

Transplant vs. Other Surgical Paths

The “gold‑standard” for end‑stage disease remains liver transplant. Yet many patients qualify for less‑invasive solutions—partial resections, laparoscopic tumor removal, or even experimental techniques—provided their liver function is still adequate.

| Parameter | Transplant Eligibility | Resection Eligibility |

|---|---|---|

| Child‑Pugh Class | Class C (or B with complications) | Class A or early B |

| MELD Score | ≥ 15 (often ≥ 20 for priority) | ≤ 12 (ideal); 13‑15 in select centers |

| Tumor Size (HCC) | Any size if within Milan criteria (≤3 cm single or ≤ 5 cm up to 3 nodules) | ≤ 5 cm solitary, sufficient future liver remnant |

| Portal Hypertension | Severe (HVPG > 12 mm Hg) → transplant preferred | Controlled or treatable; may need TIPS first |

These thresholds are not set in stone—every case is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team that weighs risks, benefits, and personal goals.

Surgery Types

Liver Transplant

A whole‑organ replacement is the definitive “cirrhosis surgery” for patients whose liver can no longer sustain life. Modern transplant programs achieve 5‑year survival rates above 70 %, and many patients enjoy a new lease on life with only a short stint of immunosuppressive therapy.

Partial Liver Resection

If a solitary tumor can be removed without leaving the remaining liver too small, surgeons may opt for a segmental or lobar resection. The key is ensuring a “future liver remnant” (FLR) of at least 30‑40 % of total liver volume for safe recovery.

Laparoscopic & Robotic Approaches

Since 2016, minimally invasive techniques have become increasingly popular for cirrhotic patients. A study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology showed that laparoscopic resections cut blood loss by 40 % and shortened hospital stays by an average of three days compared with open surgery【1†summary】.

Non‑Resectional Procedures

When resection isn’t feasible, doctors turn to other interventions:

- TIPS (Transjugular Intra‑hepatic Portosystemic Shunt) to relieve portal hypertension.

- Portal Vein Embolization or the newer ALPPS (Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein Ligation for Staged hepatectomy) to boost FLR growth before a later resection.

These aren’t “surgery” in the classic sense but are vital parts of the cirrhosis‑treatment toolbox.

Risk Assessment

Scoring Systems Doctors Use

Before any operation, surgeons run a battery of tests to predict how the liver will cope. The most common scores are:

- Child‑Pugh—uses bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, and encephalopathy.

- MELD (Model for End‑Stage Liver Disease)—focuses on bilirubin, INR, and creatinine.

- Indocyanine‑green (ICG) clearance test—a dynamic measure of hepatic blood flow.

- CT volumetry—to calculate the exact size of the future liver remnant.

Portal Hypertension’s Hidden Danger

Elevated portal pressure can turn a routine incision into a bleeding nightmare. The extra pressure compromises hepatic blood flow during anesthesia, which can precipitate rapid decompensation.

Emergent vs. Elective Surgery

Timing makes a big difference. In a Veterans Health Administration study of over 8,000 cirrhotic patients, 30‑day mortality jumped from 2 % for elective surgery to 17 % for emergent procedures【7†summary】. Even within elective cases, risk varies widely—under 1 % for inguinal hernia repair, but up to 7 % for colorectal resections.

Quick Risk‑Ladder (Infographic Idea)

Imagine a ladder: the bottom rung is Child‑A/MELD < 12 (low risk); the next rung climbs to Child‑B/MELD 12‑15 (moderate); and the top rung is Child‑C/MELD > 20 (high risk, transplant usually recommended).

Pre‑Op Preparation

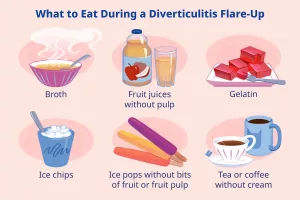

Nutritional Boost

Malnutrition is a silent killer in cirrhosis. A high‑protein, calorie‑dense diet for four weeks before surgery can raise albumin by 0.5 g/dL and cut complication rates dramatically. If you’re not a fan of chicken breast, lean soy shakes work just as well—just talk to a dietitian.

Managing Co‑Morbidities

Control diabetes, stop alcohol, optimize renal function, and adjust medications that strain the liver (e.g., NSAIDs). Some centers place patients on beta‑blockers to curb portal pressure before an operation.

Medication Reconciliation

Make a list of every pill, supplement, and herb you take. Certain anticoagulants, for example, may need to be paused a few days before surgery, whereas steroids often have to be tapered carefully to avoid adrenal crisis.

Checklist for Your Surgeon

- Confirm Child‑Pugh and MELD scores.

- Get a recent CT volumetry report.

- Schedule nutritional counseling.

- Review medication list with your hepatologist.

- Discuss anesthesia plan focused on preserving hepatic blood flow.

Intra‑Operative Strategies

Anesthesia Tips

Anesthesiologists aim to keep mean arterial pressure steady and avoid prolonged hypotension, which could starve the liver of oxygen. Many use an “low‑central‑venous‑pressure” technique to reduce bleeding.

Surgical Tricks

Surgeons employ several maneuvers that sound like they belong in a sci‑fi movie, but they’re actually life‑saving:

- Pringle maneuver—temporarily clamping the portal triad to limit blood loss.

- Selective hepatic inflow occlusion—only clamping the part of the liver you’re cutting.

- Intra‑operative ultrasound and fluorescence imaging to map vessels in real time (a tip taken from a 2016 World Journal review【1†summary】).

Open vs. Laparoscopic

Open surgery provides a big window but often means more pain and longer stay. Laparoscopic (or robotic) approaches use tiny ports, resulting in less trauma, quicker mobilization, and a lower infection risk—especially valuable for a liver that’s already compromised.

Post‑Op Care

Watch for Decompensation

The first two weeks are critical. Your team will monitor bilirubin, INR, mental status, and fluid balance daily. Any sudden rise in bilirubin or drop in platelets could signal early liver failure.

Fluid Management & Kidney Protection

Kidney injury is a hidden danger after surgery in cirrhotic patients. Keeping the right balance of fluids—neither too much nor too little—helps protect both liver and kidneys.

Pain Control Without Over‑dose

Opioids can accumulate in a failing liver, leading to sedation and respiratory depression. Many centers now favor multimodal analgesia—acetaminophen (within safe limits), gabapentin, and regional nerve blocks—to keep you comfortable without over‑relying on narcotics.

Discharge Checklist

- Stable labs (bilirubin, INR, creatinine).

- No new ascites or encephalopathy.

- Clear instructions for wound care and activity limits.

- Scheduled follow‑up with both surgeon and hepatologist within 1‑2 weeks.

New & Emerging Options (2023‑2025)

AI‑Powered Risk Models

Machine‑learning algorithms now crunch dozens of variables—age, genetics, imaging data—to predict postoperative outcomes with > 85 % accuracy. A 2023 study showed these models outperformed traditional MELD scores in identifying high‑risk patients【2†summary】.

Hybrid ALPPS + Portal Embolization

Combining two liver‑growth strategies can increase the future liver remnant by 70‑80 % in just two weeks, making resection possible for patients who previously would have needed a transplant.

Regenerative Medicine

Early‑phase trials are exploring stem‑cell infused grafts and bio‑engineered liver patches. While still experimental, these approaches promise a future where “partial liver replacement” could become a reality.

Key Takeaways

Living with cirrhosis doesn’t mean you’re doomed to surgery—or to a bleak outcome. Here’s the roadmap:

- Know your numbers. Child‑Pugh and MELD scores guide every decision.

- Transplant is the definitive cure for end‑stage disease, but many patients qualify for less‑invasive resections or minimally invasive procedures.

- Risk assessment is a team sport. Surgeons, hepatologists, anesthesiologists, and nutritionists all weigh in.

- Preparation is power. Nutrition, medication review, and controlled portal pressure can turn a risky operation into a safe one.

- New technologies are reshaping the field. From AI‑driven predictions to regenerative patches, the horizon looks hopeful.

Ultimately, the best “surgery plan” is the one that fits your personal health story, preferences, and life goals. If you’re standing at that crossroads, reach out to a liver specialist, ask questions, and remember you’re not alone. The medical community is constantly learning, and you have a voice in that conversation.

What’s your experience with cirrhosis‑related procedures? Have you or a loved one navigated a transplant or a laparoscopic resection? Share your story in the comments—your insights could help someone else feel less alone on this journey.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.