Most people assume that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is either completely safe or a guaranteed danger. The truth sits somewhere in the middle, and the balance matters for your health and peace of mind. In this post I’ll walk you through the science, the personal factors that change the odds, and practical ways to keep the benefits while keeping the risks low. Think of it as a friendly coffee‑chat where we cut through the headlines and get to the stuff that actually matters to you.

How HRT Works

First, a quick refresher. HRT replaces the estrogen (and sometimes progesterone) that your ovaries stop making during menopause. By stabilising hormone levels, it eases hot flashes, night sweats, mood swings, sleep problems, and bone loss. There are three main flavours:

| Type | What’s Inside? | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Combined (E + P) | Estrogen + Progestogen (to protect the uterus) | Most women who still have a uterus |

| Estrogen‑only | Just estrogen | Women after hysterectomy (uterus removed) |

| Tibolone | Synthetic steroid acting like both estrogen and progesterone | Often used when progestogen is a concern |

All three come as patches, gels, tablets or creams, and the dose can be tweaked. The choice of formulation is the first fork in the road that shapes your risk profile.

Cancer Evidence

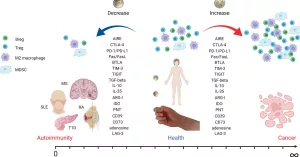

Let’s get straight to the core question: does HRT raise cancer risk? The short answer is “yes, slightly, for certain cancers, and mostly when the therapy is long‑term.” The longer you stay on combined HRT, the higher the odds of breast and ovarian cancer. When you stop, the risk gradually drops back toward baseline – usually within five years for breast cancer, a bit longer for ovarian cancer.

Key findings from the research landscape:

- Combined HRT adds about a 20‑30 % increase in breast‑cancer incidence after five years of use. The relative risk climbs to roughly 1.5‑2 × after ten years, then tapers off once the therapy ends. a study in BMJ notes that the heightened risk can linger for more than a decade after stopping.

- Estrogen‑only therapy also nudges breast‑cancer risk upward, but not as much as the combined version. However, if you still have a uterus, estrogen‑only can increase endometrial (uterine) cancer – that’s why doctors add progestogen for most women.

- Both combined and estrogen‑only regimens show a modest rise in ovarian cancer risk, which again fades after cessation. Cancer Research UK calls the increase “slight” but real enough to be mentioned.

- On the brighter side, combined HRT has been linked to a small reduction in colorectal cancer risk, and it does not affect the chance of endometrial cancer when the progestogen is included.

What does “slight increase” look like in plain numbers? Imagine a baseline breast‑cancer risk of 8 per 1,000 women aged 50‑60. Five years of combined HRT might push that to about 10 per 1,000 – a difference of two extra cases in a large group, but significant for the individual woman facing that decision.

Your Risk Factors

Risk isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all label. Several personal variables tip the scales.

| Factor | How It Changes Risk | What You Can Do |

|---|---|---|

| Age at start | Starting after 60 generally raises absolute risk because baseline cancer rates are higher. | Discuss timing with your GP; some clinicians favour starting earlier if symptoms are severe. |

| Duration of use | Longer than 5 years = higher breast/ovarian risk; >10 years = peak. | Set a stop‑date upfront; consider short “trial” periods. |

| Family history / genetics | BRCA‑positive women see a bigger absolute increase when on HRT. | Genetic counseling; possibly avoid combined HRT. |

| Body mass index (BMI) & lifestyle | Higher BMI and alcohol intake add to hormone‑related risk. | Exercise, weight management, limit alcohol. |

| Type of HRT | Combined > estrogen‑only for breast/ovarian risk. | Choose formulation that matches your anatomy and risk tolerance. |

When I was 53, my sister was diagnosed with breast cancer. That news sent me spiralling into a sea of “what‑ifs.” My doctor walked me through a personalized risk calculator, and together we mapped out the exact numbers. The exercise helped me realize that, with a low baseline risk and a planned three‑year course of low‑dose combined HRT, my added risk would be minimal. Knowing the numbers turned anxiety into confidence.

Balancing Benefits & Risks

Now that you have the data, how do you decide? Think of it as a balancing act, like a seesaw where the weight of symptoms sits on one side and the weight of cancer risk on the other.

When HRT Might Be the Best Choice

- Severe vasomotor symptoms that disrupt sleep or daily life.

- Early onset osteoporosis or a family history of fractures.

- Low baseline cancer risk (no strong family history, healthy BMI).

- Short‑term use (under five years) is feasible for you.

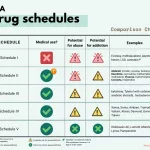

When “No HRT” Could Be Safer

- History of breast cancer, atypical hyperplasia, or a known BRCA mutation.

- Previous deep‑vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or stroke.

- Uncontrolled hypertension, severe liver disease, or active cancers.

- Long‑term desire for hormone therapy without clear stop‑date.

For those in the “no HRT” camp, alternatives exist: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for hot flashes, lifestyle tweaks (cooling the bedroom, layered clothing), and non‑hormonal vaginal moisturisers.

Practical Decision‑Making Framework

- Score your symptoms. Rate hot flashes, night sweats, mood, sleep, and bone health on a scale of 0‑10.

- Calculate your baseline cancer risk. Many health portals offer a quick questionnaire; ask your doctor to interpret the result.

- Match the HRT type to your anatomy. If you have a uterus, combined therapy is usually required; if not, estrogen‑only may be an option.

- Set a clear stop‑date. Treat HRT as a time‑limited tool unless new evidence suggests otherwise.

- Schedule regular screenings. Annual mammograms, pelvic exams, and bone‑density tests keep you ahead of any changes.

Here’s a short dialogue you can rehearse with your doctor:

You: “I’m experiencing nightly sweats that keep me awake. I’ve read that HRT can help, but I’m worried about breast cancer. What’s my personal risk, and can we try a low‑dose for six months to see how I feel?”

Doctor: “Let’s look at your family history, your BMI, and your current bone density. Based on that, your added breast‑cancer risk would be about X per 1,000 if we use combined HRT for six months. After stopping, the risk returns to baseline in about five years.”

This kind of transparent conversation makes the decision feel collaborative rather than scary.

Bottom‑Line Cheat Sheet

- Short‑term combined HRT (≤5 yr): modest ↑ breast/ovarian risk, usually outweighed by symptom relief.

- Long‑term combined HRT (≥10 yr): ↑ breast (≈1.5‑2×) and ovarian cancer; consider alternatives.

- Estrogen‑only (post‑hysterectomy): ↑ breast & ovarian risk, plus ↑ uterine cancer if uterus remains.

- Risk reversibility: breast‑cancer risk falls to baseline ≈5 yr after stopping; ovarian risk a bit longer.

- Action steps: assess personal risk, choose the lowest effective dose, set a stop‑date, keep up with screenings.

Conclusion

Understanding HRT cancer risk isn’t about scaring yourself; it’s about empowering you with the facts you need to make the right choice for your body and lifestyle. The increase in cancer odds is real but generally small, especially when you keep the therapy short and tailored to your needs. By asking the right questions, weighing the personal risk factors, and staying on top of regular check‑ups, you can enjoy the relief HRT offers without living in fear of the numbers.

What’s your experience with menopause symptoms? Have you tried HRT, or are you leaning toward non‑hormonal options? Drop a comment below, share your story, or ask any lingering questions—you’re not alone on this journey, and together we can navigate the crossroads of relief and risk with confidence.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.