Ever wonder what “blood doping” actually means and why it shows up in every headline about endurance athletes? In a nutshell, it’s a set of tricks athletes use to load their bloodstream with extra red blood cells so more oxygen can reach the muscles. The result? A short‑term boost in stamina, speed, or recovery.

Sounds tempting, right? The reality, though, is a lot messier. The health dangers, legal penalties, and the fact that anti‑doping tech is getting sharper every day make blood doping a risky gamble. Below we’ll walk through the science, the methods, the risks, and how the sport‑governing bodies sniff it out—all in a friendly, coffee‑chat style.

Quick Answers Overview

What is blood doping?

Blood doping is any practice that artificially raises the number of red blood cells (RBCs) or the total hemoglobin in an athlete’s bloodstream. More RBCs = more oxygen transport = better endurance performance. The World Anti‑Doping Agency (WADA) defines it as “the use of products that enhance the uptake, transport, or delivery of oxygen to the blood.”WADA FAQ

Should you consider it?

The short answer: No. While a 2‑5 % lift in VO₂max can shave seconds off a marathon, the health complications (blood clots, stroke, heart attack), career‑ending bans, and loss of credibility far outweigh the fleeting advantage.

Why Athletes Use

Performance‑Boosting Science

Red blood cells are the body’s oxygen taxis. When you add more taxis, each delivery run becomes quicker, allowing muscles to work longer before fatigue hits. Research from the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that when total RBC mass rises enough, athletes see measurable improvements in maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) and lactate buffering.Jones & Pedoe review

Typical Sports That Turn to It

Think of any sport that runs on endurance miles or minutes of sustained effort: marathon running, long‑track cycling, rowing, triathlon, even cross‑country skiing. A quote from Mayo Clinic’s Michael Joyner captures it perfectly: “Blood doping reduces fatigue by increasing the supply of oxygen to the exercising muscles.”Live Science

Psychological Factors

Pressure to win, lucrative sponsorships, and the fear of falling behind can push athletes toward shortcuts. It’s a classic “win‑at‑any‑cost” mindset, and that’s exactly why the anti‑doping community keeps a close eye on endurance disciplines.

Main Doping Methods

Autologous Blood Transfusion

How it works: The athlete draws a pint of their own blood months before competition, stores it (often frozen), and then re‑infuses it shortly before the event. This temporarily spikes the RBC count without the risk of blood‑type mismatches.

Detection challenges: Because the blood is the athlete’s own, labs must look for “biological passport” anomalies—sudden jumps in hemoglobin or reticulocyte percentages that don’t match the athlete’s baseline.USADA FAQ

Homologous Blood Transfusion

Here a donor’s blood (matched type) is used. The giveaway is tiny antigen differences that show up under flow‑cytometry. Modern labs can spot these mismatches, making homologous transfusions riskier than autologous ones.

Erythropoietin (EPO) & ESA Injections

EPO is a hormone naturally made by the kidneys to tell bone marrow to crank out more RBCs. In the 1990s, athletes began injecting synthetic EPO to turbo‑charge their red‑cell production. While EPO is lifesaving for kidney‑failure patients, abusing it forces the body to overproduce cells, thickening the blood.

Detection used to be a nightmare because injected EPO is chemically identical to the body’s own hormone. Today, electrophoretic profiling and iso‑form separation can reliably differentiate the two.USADA FAQ

Artificial Oxygen Carriers (Blood Substitutes)

These are lab‑crafted molecules—modified hemoglobin solutions or perfluorochemicals—that bind oxygen and circulate like blood. They’re technically “blood doping” because they replace the oxygen‑carrying function, but they’re far less common due to cost and detection complexities.

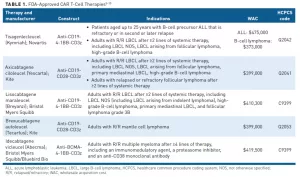

| Method | How It’s Done | Typical Detection Technique | Key Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous Transfusion | Own blood drawn, stored, then reinfused | Biological passport anomalies, hemoglobin spikes | Blood‑clotting, infection risk from storage |

| Homologous Transfusion | Donor blood matched by type | Flow‑cytometry antigen mismatch | Allergic reaction, disease transmission |

| EPO/ESA Injection | Synthetic hormone injected | Iso‑form electrophoresis, urine tests | Hypertension, stroke, heart attack |

| Artificial Carriers | Infusion of synthetic hemoglobin or perfluorochemicals | Mass spectrometry, specific marker assays | Kidney strain, unknown long‑term effects |

How Performance Improves

Oxygen‑Transport Gains

Boosting RBC count lifts VO₂max by roughly 2‑5 %. That might sound modest, but in elite competition a 3 % edge can be the difference between a gold medal and a fourth‑place finish. Imagine a marathon runner shaving three minutes off a 2:10:00 finish—suddenly they’re on the podium.

Fatigue‑Delay & Recovery

More oxygen means the muscles produce less lactate, delaying that burning sensation that forces you to slow down. A 1989 literature review highlighted that athletes who successfully doped saw improved lactate buffering and better thermoregulation, letting them sustain higher intensities longer.

Real‑World Case Studies

Perhaps the most infamous example is Lance Armstrong. In a 2012 interview with Oprah, he admitted to using multiple blood‑doping techniques, including autologous transfusions and EPO. The fallout—seven stripped Tour de France titles—remains a cautionary tale.

Going further back, Finnish distance legend Lasse Viren dominated the 1970s. While official rules didn’t ban blood doping until 1986, many suspect his record‑breaking runs were aided by early transfusion practices.Encyclopedia.com

Health & Career Risks

Medical Complications

Blood thickening (hyperviscosity) raises the risk of thrombosis, heart attack, stroke, and pulmonary embolism. The USADA health warning stresses that athletes who misuse EPO “thicken the blood, leading to an increased risk of several deadly diseases.”USADA

Repeated transfusions can also overload the kidneys and cause chronic hypertension. For many, the damage persists long after the doping career ends.

Legal & Ethical Consequences

WADA’s Prohibited List makes blood doping a violation at all times. Getting caught typically results in a minimum two‑year ban; repeat offenders face lifetime bans and the stripping of medals. Sponsors, too, vanish overnight—remember how quickly companies fled from Armstrong after his confession?

Long‑Term Uncertainty

Even if an athlete evades detection, the physiological strain can linger. Elevated hematocrit levels may stay high, increasing the risk of cardiovascular events later in life. The hidden cost is often a shortened, less healthy post‑sport life.

Detection & Testing

Biological Passport & Hematological Markers

Instead of testing for a specific drug, the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) tracks longitudinal blood data—hemoglobin, reticulocytes, OFF‑score, etc. Sudden spikes trigger a “targeted test” and possible sanctions.

Direct Lab Tests

For EPO, labs now use iso‑form electrophoresis to separate synthetic from natural hormone. Homologous transfusions are uncovered via flow‑cytometry that spots donor antigens. Blood‑substitutes leave distinct molecular fingerprints detectable by mass‑spectrometry.

Emerging Technologies

A 2025 report from USC’s Viterbi School highlighted AI‑driven pattern recognition applied to athletes’ biometric data. By learning what normal variation looks like for each individual, the system can flag suspicious deviations earlier than traditional methods.

Final Thoughts Summary

Blood doping delivers a measurable oxygen advantage, but it comes with a heavy price: serious health hazards, career‑ending bans, and a tarnished legacy. Modern anti‑doping science—biological passports, sophisticated lab assays, and emerging AI tools—makes the odds of getting away with it slimmer than ever. If you’re an athlete chasing performance gains, the safest, most sustainable route is to focus on proven training, nutrition, and recovery methods that respect both your body and the spirit of fair competition.

What are your thoughts on the balance between cutting‑edge performance science and ethical sport? Have you ever encountered teammates or friends wrestling with the temptation of shortcuts? Drop a comment below, share your experiences, or ask any lingering questions—you’re not alone in navigating this complex world.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.