Some toddlers adopt a duck-footed walk as they gain confidence in their new skill — this is also called out-toeing. In this gait, the toes point outward instead of straight ahead, producing a waddling appearance.

Out-toeing can also appear for the first time during adolescence, the teen years, or in adulthood. It’s not always worrisome, but it helps to distinguish between a normal duck-footed gait and a problem that affects walking mechanics.

Continue reading to learn what causes this gait, when to seek medical advice, and what options exist for management.

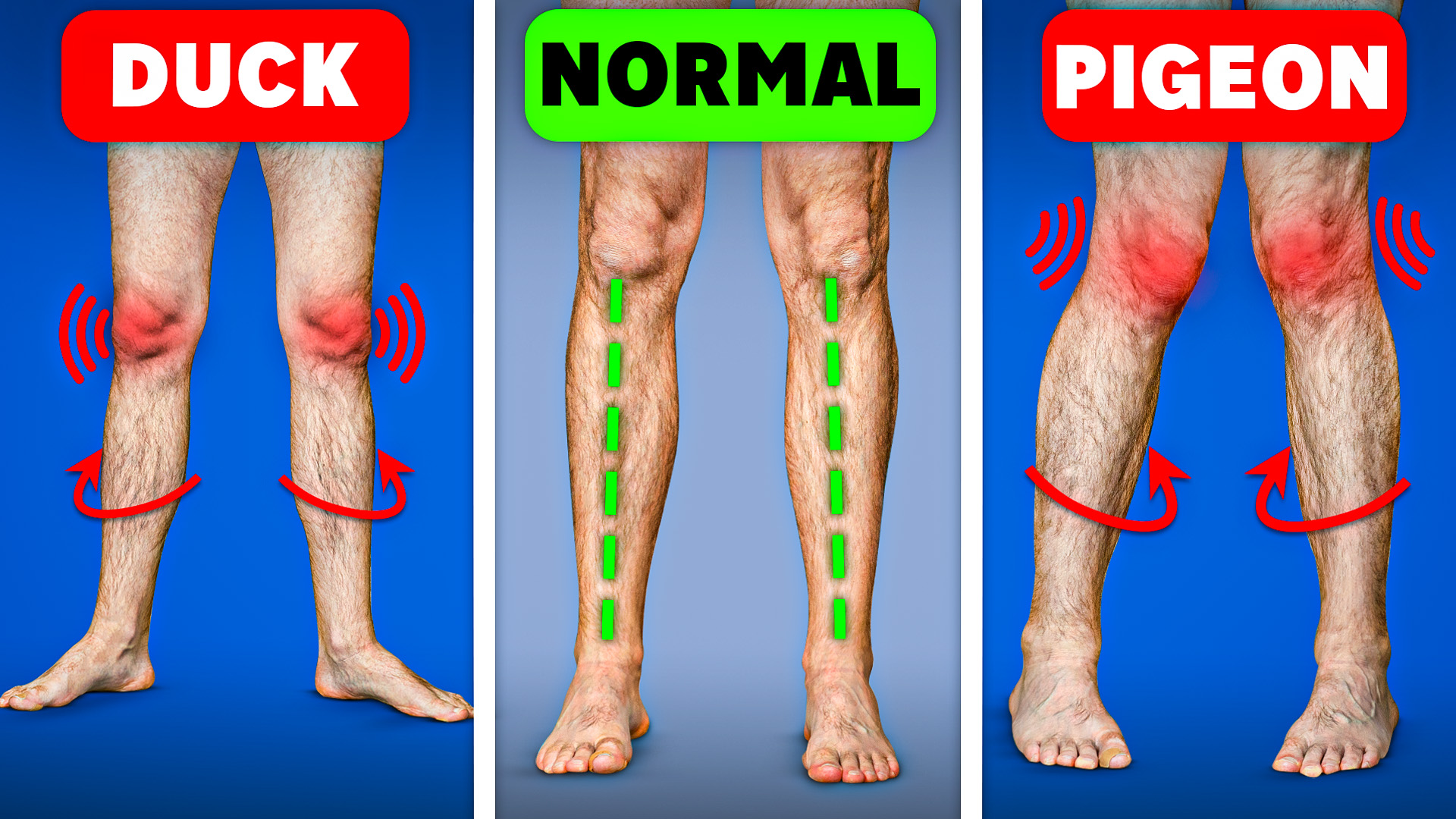

What does duck-footed mean?

Out-toeing is a torsional variation. It generally happens when one of the long bones in the leg rotates outward, causing the foot to angle away from the midline:

- tibia: the bone between the ankle and knee

- femur: the bone between the hip and knee

Out-toeing may affect one leg or both. In many young children it’s temporary and resolves on its own, but duck-footedness can persist into adolescence or adulthood in some people.

Having flat feet can also give the impression of out-toeing.

Is this the opposite of pigeon-toed?

You’re likely familiar with in-toeing, or being pigeon-toed, which is essentially the reverse of duck-footedness.

With in-toeing, the toes point inward rather than outward when walking.

What are the signs of being duck-footed?

Out-toeing can make a child appear to sway side to side while moving. You may also see the knees splay outward.

Out-toeing usually isn’t painful and typically doesn’t impede a child’s ability to walk, run, or be active.

The gait may be more pronounced during running than walking. Parents might notice shoes wearing more on the outer edges or visible scuffing there.

To check for out-toeing in adults, stand naturally with feet about a foot apart and look down — if your toes point outward rather than forward, you likely have a duck-footed stance.

Another quick check:

- Lie on your back.

- If your feet and knees rotate outward together, tight hip muscles might be contributing to out-toeing.

What causes duck-footedness?

Common reasons children develop out-toeing include:

- family tendency toward a duck-footed stance

- the fetal leg position in utero

- how the legs rest during infancy

- flat feet

Less frequent causes include:

- congenital bone abnormalities

- slipped capital femoral epiphysis, a hip growth-plate disorder where the femoral head shifts backward

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

Capital femoral epiphysis develops in adolescents who are still growing and is sometimes described as a problem of the hip growth plate.

In adults, out-toeing can stem from:

- trauma to the leg, hip, ankle, or foot

- tight muscles in the hips or legs

- poor postural habits

- a sedentary lifestyle that causes an anterior pelvic tilt (a forward tipping of the pelvis)

Anterior pelvic tilt in adults

An anterior pelvic tilt tightens hip muscles, rotating the femur outward and potentially producing a duck-footed gait.

When should you worry?

In adults, out-toeing ranges from mild to pronounced. If it doesn’t limit activities like walking, running, or swimming, it’s usually not alarming.

If you’re uneasy about your child’s walking pattern at any stage, consult their doctor.

Most children outgrow out-toeing by ages 6 to 8. See a clinician sooner if your child’s gait persists past that age or if any of the following occur:

- Your child frequently limps or falls while walking or running.

- Your child has persistent or episodic pain in the legs, hips, or groin — this could signal slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Pain may be mild, severe, constant, or sudden.

- Your child suddenly cannot walk (this may also indicate slipped capital femoral epiphysis).

- Your condition is severe and provokes pain, loss of balance, or instability.

Are there home treatments for out-toeing?

Mild out-toeing often improves with at-home approaches. Try these methods:

Adjust your foot positioning

Be mindful of how you place your feet when standing and moving. Re-training your stance can reduce outward toeing.

Try orthotic inserts

Orthotic shoe inserts that support and raise the arch may help stabilize the heel and improve alignment.

Stretching and strengthening

Stretching the hips and hamstrings can benefit mild cases. Below are simple stretches you can do at home.

Wall stretch

- Put a foot riser or several sturdy books about 2 feet from a wall.

- Stand on the riser so your heels hang off the back edge.

- You’ve achieved the correct position when your arches are supported but your heels are free.

- Lean toward the wall with your hands at shoulder height and arms straight to support your body.

- Lift each foot up and down alternately to stretch the calf and foot.

Tennis ball roll

- Sit on the floor with legs extended.

- Place a tennis ball under one calf and roll it back and forth for about 2 minutes.

- Enhance the stretch by flexing the foot while rolling.

- If the outer leg feels tight or sore, try rolling the ball along that side.

- Repeat for the opposite leg.

- Do this several times daily.

Piriformis stretch

- Lie on your back with knees bent and feet flat hip-width apart.

- Cross one ankle over the opposite thigh just above the knee.

- Press down gently with the crossed ankle and hold for 60 seconds.

- You should sense a mild stretch through the thigh, hip, and lower back.

- Switch sides and repeat.

For information about foot shapes that may relate to gait, see types of feet.

When is a doctor visit needed?

Any pain, limited mobility, or persistent discomfort warrants contacting a healthcare provider for both children and adults. You should also call the pediatrician if your child limps or falls often.

Consider visiting a doctor or physical therapist before starting home treatments. A professional can determine whether muscle tightness or rotation of the tibia or femur is causing the out-toeing and recommend the most effective exercises.

How is duck-footedness evaluated?

Your provider may use several approaches to diagnose out-toeing:

- History: asks how long the issue has been present and any events that might explain it, plus family history.

- Physical exam: focuses on legs, hips, and feet to assess tightness, flexibility, and range of motion.

- Rotation assessment: evaluates the degree of bone rotation by examining angles between feet and legs, often with you lying on your stomach and knees bent.

- Footwear inspection: your clinician may inspect your shoes and observe you walking in your usual footwear.

- Running test: you may be asked to run so the doctor can see any side-to-side waddling and foot position during motion.

- Imaging: X-rays or MRI may be ordered if a serious issue like slipped capital femoral epiphysis is suspected.

What medical treatments exist?

Possible clinical options include:

- Watchful waiting: for children under age 6, a doctor may recommend monitoring to see if the gait self-corrects.

- Physical therapy: a therapist can guide exercises to retrain leg and foot positioning and relieve hip tightness.

- Surgery: if a bone deformity or slipped capital femoral epiphysis is diagnosed, surgical intervention might be advised.

Could out-toeing cause complications?

If significant out-toeing is ignored, it can eventually contribute to other problems, such as:

- muscle wasting in the lower legs and gluteal muscles

- knee injuries

- ankle injuries

- flat feet

- foot pain

- piriformis muscle damage that could lead to sciatica

Bottom line

Out-toeing, or duck-footedness, is characterized by feet that angle outward rather than forward.

It’s most typical in toddlers and young children, who usually outgrow it by about age 8. Adults can develop it due to inactivity, postural issues, injury, or other factors.

The condition is seldom serious and often improves with home-based measures. Contact your child’s pediatrician if you have concerns about their gait.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.