You woke up to headlines about bird flu outbreaks in cows. Wait… cows? Since when do cows get the bird flu?

Outbreak Origins

The Day Bird Flu Slipped Into Cattle Country (You Never Saw It Coming)

Let me take you back to March 2024. In Texas, a farmer noticed two cows acting… off. Lactating cows with thick, discolored milk. Appetite tanks. No appetite. No milk. This wasn’t a bad case of the munchies—it was H5N1 bird flu.

We all thought bird flu was just for birds. But according to USDA, by April 8, 2024, the virus had spread to 443 cows, and by July 2025, 17 states were reporting infections. Ohio got hit after cows were transported from Texas. It’s wild to see bird flu behaving more like a cattle rustler than a poultry disease, right?

The virus is the same 2.3.4.4b clade causing global chaos. But dairy cows? Not dead like poultry. Just… different. Slower. Sneaky. Like the flu decided to wear a cow costume.

Why Cows of All Animals?

Okay, real talk—cows are not birds. They’re not even flighty. So what gives?

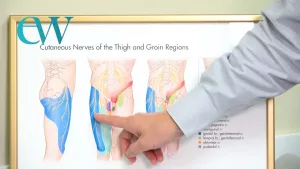

Experts from a University of Minnesota study looked into this. Turns out cows drink raw milk. Yes. The udder is a prime viral playground—and it’s full of sialic acid receptors. These receptors are like VIP entry points for the virus.

A Chinese research team found that self-nursing among cows allowed the virus to invade through teats. It’s not just airborne. It’s… milkborne? Kinda. The virus found a backdoor into cow biology—and now we’re scrambling to keep it from becoming a repeat offense.

How the Virus Acts in Cows

Signs You’re Dealing With H5N1 (And They’re Not Like Chicken Coop Outbreaks)

Your cow looks like she’s running on empty. She’s sluggish. Got a fever. Her milk production plummeted—like, straight off the deep end. And milk? Looks more like colostrum or mastitis goop—thick, off-colored.

Most recover in a few days. But pastured animals? No dice. Not yet.

What About Cows Who Seem Fine?

This is the really messy part. Some cows walk around with the virus and zero symptoms. No fever, no milk drama. Quietly contagious. Imagine your herd walking around with the flu, infecting others, and you don’t even know it.

USDA tested 768 herds in California alone, and you know what? Most recovered. Mortality was under 2%. But with over 1000 confirmed herds by early 2025… even 2% starts adding up.

Transmission: It’s Not Just Birds or Needles

The Role of Flies (Yes, Gross—But Important)

Let me know if you’ve ever heard something nuttier than this: house flies are mechanically spreading the virus across farms. No, they’re not infected, but they walk across milk residue, contaminated equipment, and then BAM—virus gets a free ride to the next barn.

I know. Flies on cow udders. Fly season is already enough of a nightmare without viral hitchhikers. That’s why a 2025 study from Arkansas State University is calling for extra fly control in dairy operations. They didn’t spread H5N1 directly—more like delivery trucks that don’t clean their tires in between.

‘Milk Snatching’—It’s Real, It’s Contagious

Cows are sneaky. You know how they sneak into each other’s stalls for an extra sip of feed? Turns out they’re milk nipping too. A new study in National Science Review showed milk-drinking behavior spreads the virus mouth-to-teat. And calves? Even more effective spreaders. One sick nursing baby cow equals ten more cows in the next stall.

Crazy how nature works.

Protecting Your Herd (And Yourself)

Biosecurity That Goes Beyond Boots and Overalls

- Change clothes between farms—just like your last visit to a sick friend. You wouldn’t wear yesterday’s jacket after touching a sneezing buddy. Same vibe.

- Sanitize milking equipment after each cow. Virus survives for days on surfaces. That milking machine? Viral playground.

- Use quarantine pens for any incoming lactating cows. 30 days. It works for your pets, works for cows too.

USDA isn’t just telling you to “clean better”—they’re offering cash incentives to beef up biosecurity. Because if you’re losing milk production, losing cows, it’s not just about being “thorough.” It’s about survival.

Testing Before Moving Cows—Because Movement Means Spread

Here’s the deal: cows can be quiet carriers. One sneeze, a shared truck, and that clean herd in Arizona? Now on the CDC radar thanks to a milk-sampling system. That’s what happened in early 2025 with the first D1.1 genotype detected in dairy farms in Nevada.

So yes, USDA’s Federal Order of April 2024 says no interstate movement without test results. But even that’s not foolproof—some herds still slipped through. Not the cows’ fault. The system’s still playing catch-up.

Worker Safety (Even If You’re Not a Cow Whisperer)

Seriously—this isn’t just about your cows. Let’s talk human risk. As of this year, over five dairies in Texas and three in Ohio have linked cow workers with bird flu exposure.

You might’ve heard about the human who got infected in Texas last spring—first known cow-to-human spread. CDC still says the public’s at low risk, but if you’re walking among infected animals, the gloves come on. Literally. Masks, too.

Ohio Outbreak: A Closer Look

Cows from Texas, Problems in Ohio

Let’s zoom into Ohio. March–April 2024. A 3,876-cow farm brings in 42 fresh cows from Texas. By day 10, the milk tank’s down by 80%.

Let me re-read that last part: 80% loss in milk in ten days. That’s not just a dip—it’s a nosedive.

Now, Ohio’s outbreak was genotype B3.13. By mid-2024, Nevada and Arizona saw D1.1—a new version of the same virus but adapted for wild birds. That’s evolution in fast-forward. And the virus? Still using milk as a transmission highway.

Livestock Losses and Economic Impact

| Herd | Milk Reduction (70 days post-outbreak) | Culling Rate (%) | Revenue Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ohio (2024) | ↓ 75% | ~1.5% | $850,000 estimated |

| Nevada (2025) | ↓ 42% | ~1.9% | $480,000 estimated |

| Arizona | ↓ 67% | ~1.6% | $720,000 estimated |

Source: USDA APHIS Reports, April 2025

Vaccines and Solutions Still Cooking

Detecting D1.1 and B3.13—They’re More Than Lab Codes

Genotypes are the flu’s fingerprints. B3.13 was dominant early. Then, by early 2025, scientists picked up D1.1 cases in Arizona and Nevada. That version’s more common in wild birds this year—so either it’s adapting… or cow barns are turning into avian zones.

Veterinarians and researchers are tracking mutations like weather forecasters. Genotyping changes aren’t just lab chatter. It shows where control efforts need to focus.

Two Vaccines That Show Real Hope (But Are Still on the Shelf for Now)

We’re not just sitting back hoping for the best. As of 2025, two vaccines in phase: an inactivated H5 and a DNA-based vaccine. Both reduced infection rates in lactating cows.

Here’s the kicker: vaccines work best when the virus hasn’t changed up its genetics. Since D1.1’s got a different viral pattern, we might need cow-specific strains. That’s where the USDA’s pushing.

Why This Outbreak Matters (Even If You’re Not in a Dairy)

Food Safety? We’ve Got the Basics Covered

Let me reassure you—pasteurization kills the virus stone dead. You’re good to drink that milk. Raw milk is riskier. But hey, we’ve heard about unpasteurized cheese making people sick before, right? Same story.

Beyond milk? Beef remains safe, as long as you cook it well. This isn’t salmonella—it’s a virus that doesn’t linger on a well-done steak. USDA’s got your back on this one.

Monitoring Systems Are on the Job—Here’s How You Benefit

CDC and USDA aren’t napping while H5N1 is loose on farmland. FluView reports are updated monthly. Cows aren’t the priority yet, but the data pipeline’s open for tracking.

Farmers and veterinarians are the true eyes and ears of this outbreak. Without real on-ground reports on feed behavior or milk quality, we’d be flying blind. And frankly, this one cow flu isn’t the first zoonotic virus to test how closely linked livestock and humans truly are.

So here’s a question for you: what do you think will happen if this spreads even further?

Closing Thoughts: Staying Ahead of an Unpredictable Virus

I know—avian flu in cows felt surreal at first. But nature keeps throwing curveballs, and we catch ’em the best we can. Here’s the real deal: this isn’t a food safety apocalypse. It’s a lesson in biosecurity. In adaptability. In how a virus we thought only attacked chickens… learned to slip into a cow barn. Through flies. Through milk. Maybe through something we haven’t even discovered yet.

Stay aware. Stay safe. And if you’re farming—don’t be shy when it comes to testing. If Ohio’s outbreak taught us anything, it’s that one healthy cow isn’t proof you’re clear.

If you found this helpful or have your own story to share—hit reply, I’m curious. Because this isn’t just a story for the USDA or Texas farms. It’s a real moment in time that any farmer might walk into.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.