The so-called “Barbie doll” aesthetic describes vulvas with tucked, narrow folds that are barely visible, creating the impression of a very tight vaginal opening.

Other descriptors include “clean slit,” “symmetrical,” or “perfect.” Some researchers also refer to this as a particular aesthetic ideal.

Increasingly, women are requesting this appearance when pursuing procedures commonly marketed as vaginal rejuvenation, or more broadly, female genital cosmetic surgery.

“Once my husband and I were watching a TV show

together and a character made a joke about a woman with my type of labia. I

felt humiliated in front of my husband.”

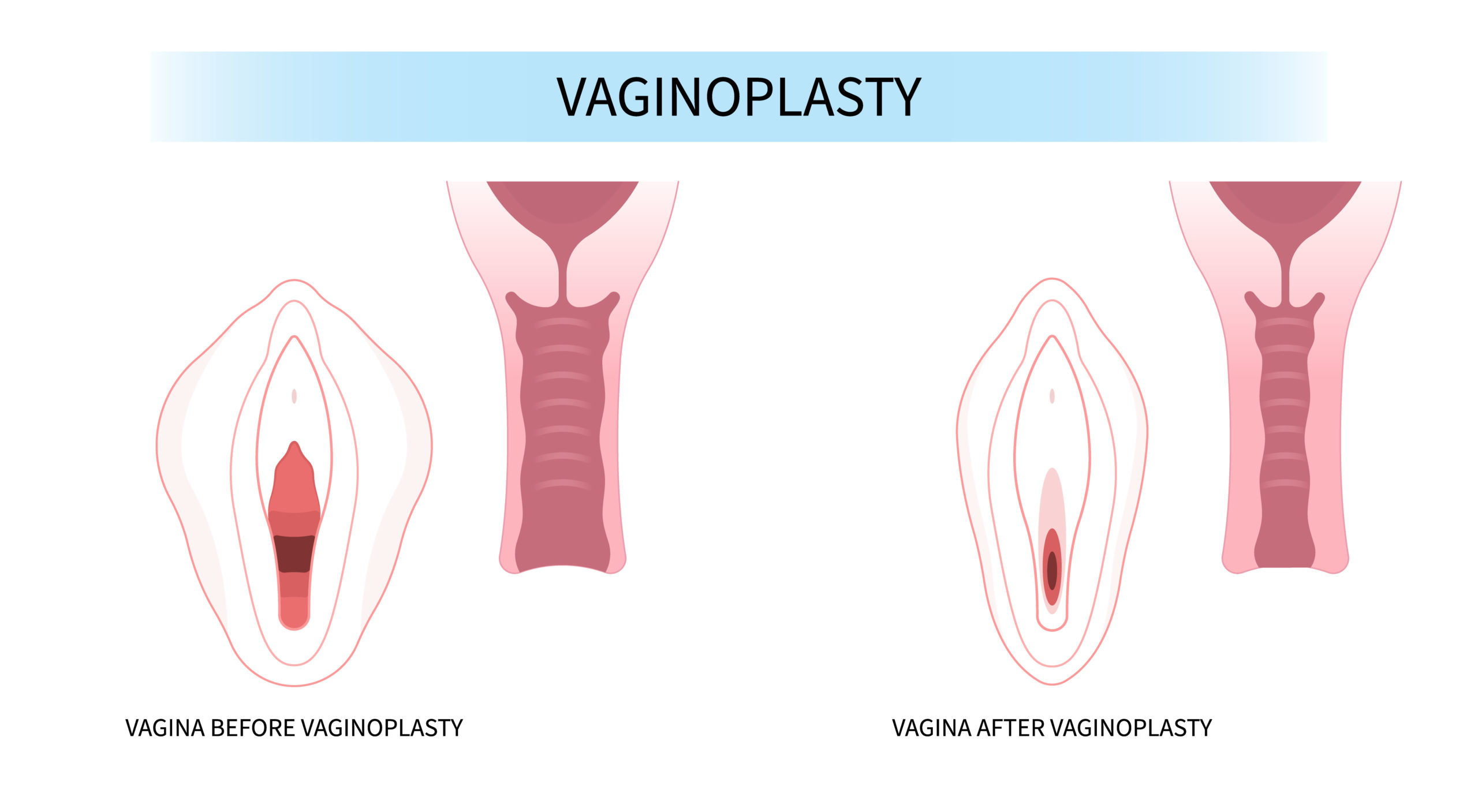

Before exploring the psychological drivers behind these requests and their origins, it’s useful to clarify the terminology involved.

The world of vaginal rejuvenation

The term “vagina” is often misapplied in popular media. While “vagina” technically refers to the internal canal, people frequently use it to describe the labia, clitoris, or mons pubis. As a result, “vaginal rejuvenation” has become an umbrella phrase encompassing a wider range of interventions than the word strictly denotes.

A web search for vaginal rejuvenation will return both surgical and non-surgical treatments for the external and internal female genitalia. These include:

- labiaplasty

- vaginoplasty or “designer vaginoplasty”

- hymenoplasty (sometimes called “re-virginizing”)

- the O-shot, or G-spot amplification

- clitoral hood reduction

- labial brightening

- mons pubis reduction

- vaginal tightening or resizing

Many of these procedures—and the motives for undergoing them—are contentious and raise ethical questions.

Researchers have observed that these interventions are primarily pursued for cosmetic or sexual reasons, with few being medically necessary.

More recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning to companies promoting vaginal rejuvenation services.

These adverts often promised to “tighten and refresh” women’s vaginas. Some targeted postmenopausal concerns—like vaginal dryness or painful intercourse—with claims of improvement.

The challenge is this: in the absence of long-term research, there’s scant evidence that these treatments are effective or safe.

An analysis of 10 women’s magazines

found that in images of naked women or those in tight clothing, the pubic region

is typically hidden or depicted as a smooth, flat curve between the thighs.

While FDA oversight may push the industry toward safer practices, vaginal rejuvenation procedures continue to gain popularity.

A 2017 report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons noted a 39 percent rise in labiaplasty operations in 2016—more than 12,000 procedures. Labiaplasty commonly involves trimming the labia minora (inner lips) so they don’t extend beyond the labia majora (outer lips).

However, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises caution, criticizing marketing that suggests these surgeries are routine or broadly accepted as misleading.

For sexual dysfunctions, ACOG recommends a careful clinical assessment and thorough counseling about potential complications and the limited evidence supporting these procedures as treatments.

Why do women seek out such procedures?

A 2014 study in Sexual Medicine found that the majority of individuals pursuing vaginal rejuvenation cite emotional reasons—chiefly feelings of self-consciousness.

Here are a couple of quotes from women who participated in the study:

- “I hate mine, hate, hate, HATE it! It’s like a

tongue sticking out for heaven’s sake!” - “What if they told everyone in school, ‘Yeah,

she’s pretty but there’s something wrong down there.’”

Dr. Karen Horton, a San Francisco plastic surgeon who performs labiaplasties, concurs that aesthetic concerns often motivate patients.

“Women want their labia minora to be tucked, neat, and unobtrusive, and don’t like seeing them protrude,” she explains.

One patient told her she simply “wanted it to look prettier down there.”

Where does the idea of ‘prettier’ originate?

A lack of education and frank discussion about the normal appearance and function of female genitalia means the pursuit of an idealized vagina may be never-ending.

Some women turn to interventions like labiaplasty or the O-shot to correct features they dislike or consider abnormal. Often, those negative perceptions stem from media images—such as airbrushed depictions in women’s magazines—that present unrealistic genital norms.

Those portrayals can implant insecurities and skew expectations about what is “normal,” potentially driving the rise in cosmetic genital procedures.

An analysis of ten women’s magazines revealed that in photos of nude or snugly clothed women, the pubic region is often concealed or drawn as a seamless, flat curve between the thighs.

There’s rarely any sign of protruding inner labia—or even the contour of the labia majora.

Presenting labia as tiny or absent—a wholly unrealistic depiction—can mislead women about how their own genitals should look.

“My patients have no idea what ‘normal’ vulvas are

supposed to look like and rarely have a solid idea about what their own looks

like.” — Annemarie Everett

Some observers, like Meredith Tomlinson, blame pornography for promoting an idealized vulva.

“Where else are we seeing close-ups of another woman’s private parts?” she asks.

That argument has weight: Pornhub reported more than 28.5 billion visits over the past year, and its annual review showed “porn for women” as the top search phrase in 2017, with a 359 percent increase in female users.

Researchers at King’s College London have suggested that the growing visibility of porn may contribute to rising rates of vaginal rejuvenation, given unprecedented online access for both men and women.

“Honestly, I think the idea of the ‘perfect vagina and vulva’ stems from a lack of accurate information about what vulvas look like,” says Annemarie Everett, a certified women’s health specialist and pelvic and obstetrics physical therapist.

“If pornography and the narrow notion that vulvas should be small and dainty are our only references, anything that deviates from that seems unacceptable, and we lack ways to challenge that belief,” she adds.

But porn might not be the sole culprit.

A 2015 study examining women’s genital satisfaction, interest in labiaplasty, and factors influencing those attitudes found that while pornography consumption correlated with openness to labiaplasty, it did not predict overall genital satisfaction.

These results suggest pornography is only one of several influences, and that other predictors should be considered in future research.

More women than men listed their dislikes than likes

about their vulva and vagina.

In short, pornography may contribute but is unlikely to be the primary driver. Another element is women’s perceptions of what men prefer and what constitutes a “normal” vulva or vagina.

“My patients have no idea what ‘normal’ vulvas are supposed to look like and rarely have a solid idea about what their own looks like,” Everett reiterates. “Culturally, we hide our anatomies and spend little time educating young people about the range of normal.”

Little girls who only see Barbie’s perfectly sculpted, plastic “V” as a model for the vulva aren’t helped by that representation.

More education can promote body positivity

A study surveyed 186 men and 480 women about their likes and dislikes regarding vulvas and vaginas to better understand cultural and social messages about female genitalia.

Participants were asked, “What things do you dislike about women’s genitals? Are there certain qualities that you like less than others?” Among men’s responses, the fourth most common was “nothing.”

The most frequent dislikes were smell and pubic hair.

One man commented, “How can you dislike them? No matter what the individual topology of each female is, there is always beauty and uniqueness.”

Men also often expressed appreciation for diverse genital appearances. “I love the variety of shapes and sizes of the labia and clitoris,” one wrote.

Another offered a detailed preference: “I like long, smooth, symmetrical lips — something voluptuous, that captures the gaze and imagination. I like large clits, but I don’t get as excited over them as I do over lips and hoods. I like a vulva to be big, lips unfurled, and deep in its cleft.”

In fact, the study found that women listed more dislikes than likes about their vulvas and vaginas, leading the authors to suggest: “Women may be internalizing negative messages about their genitals and focusing on critiques.”

Six weeks and $8,500 dollars of out-of-pocket expenses

later, Meredith has a healed vulva — and a healed sense of self.

Those negative messages can be harsh, and they sting more when there is no single “perfect” vulva.

Men who voiced dislikes used blunt terms like “big,” “flappy,” “flabby,” “protruding,” or “too long.” One woman recalled a male partner recoiling at her larger inner lips, calling them a “meat curtain.” Another man said, “I think hairy genitals on a woman is gross, it makes her look neglectful of her private area.”

If magazines depicted real women’s vulvas in all their variety—large, small, hairy, or smooth—these hurtful judgments might carry less weight.

Greater education about how a woman’s vulva and vagina can change across her life could foster more body acceptance and positivity.

Finding a balance between external and internal pressures

But what about people who grew up without genital education or who feel an urgent need for vaginal rejuvenation now?

Meredith, introduced earlier, had long been self-conscious about her labia because her inner labia protruded several centimeters beyond her outer lips.

“I always suspected I was different, but when I was naked around other girls I realized I truly was,” she says.

Consequently, Meredith avoided swimsuits, fearing exposure of her inner labia. She also shunned tight yoga pants because they revealed the shape of her vulva.

When she wore jeans she used a maxi pad to prevent chafing. “Once, after a day of biking,” she recalls, “my labia were bleeding. It was excruciating.”

Her insecurity affected relationships too; she worried about partners laughing, making crude jokes like “roast beef vaginas,” or being turned off by her anatomy.

Even after marriage, Meredith still felt vulnerable.

“Once my husband and I were watching a TV show together and a character made a joke about a woman with my type of labia,” she remembers. “I felt humiliated in front of my husband.”

After reading an online article, Meredith discovered the term “labiaplasty”—a surgical procedure to reduce the size of the inner labia.

“This was the first time I learned there was a way to change what I’d been struggling with and that others experienced the same thing,” she says. “It felt liberating.”

She consulted with Dr. Karen Horton, who advised on where to trim. “I didn’t have a picture, but Dr. Horton made suggestions for where to trim my inner labia,” Meredith recounts.

Her husband neither suggested nor pressured the surgery. “He was surprised but supportive,” she recalls. “He said he didn’t care and that I didn’t have to do it, but he would support me either way.”

Meredith underwent a labiaplasty—a one-day operation she describes as “simple, fast, and straightforward,” though it requires general anesthesia. Dr. Horton recommended a week off work, three weeks off exercise, and six weeks without sex.

Meredith returned to work the next day.

Six weeks and $8,500 out of pocket later, Meredith has a healed vulva—and a restored sense of self.

“I have no regrets; it was absolutely worth it,” she says. “I’m not hiding anymore. I feel normal.” She now wears bikinis, no longer needs a maxi pad with jeans, and cycles long distances again.

Since the operation, Meredith and her husband seldom discuss it. “I did it entirely for myself. It was a personal choice.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.