Atypical anorexia resembles anorexia nervosa in its restrictive eating behaviors and psychological distress, yet even after unhealthy weight loss, individuals with atypical anorexia keep a body mass index (BMI) within or above the “normal” range.

Eating disorders present in many different ways. It may surprise some to learn that anorexia nervosa, commonly associated with very low body weight from disordered eating, can also occur in people who are in moderate or larger bodies.

This presentation, called atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN), shares the same symptoms as anorexia nervosa (AN). The key difference is that in AAN the person undergoing harmful weight loss still has a BMI that falls in the “normal” range or higher.

What is atypical anorexia nervosa?

AAN is a diagnostic subtype included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR), under the category “Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED).”

The diagnostic criteria for AAN mirror those of AN except in regard to weight. In atypical anorexia, a person’s weight remains in the “normal” range or higher despite notable weight loss. Because of this, clinicians often overlook or misrecognize the disorder, which can delay appropriate care.

Individuals with AAN can experience medical and psychological complications that are similar to—or in some cases more severe than—those seen in typical AN, including conditions like hypophosphatemia (low blood phosphorus).

These complications often arise from rapid weight loss caused by behaviors such as severe dietary restriction, self-induced vomiting, or other forms of disordered eating.

Is atypical anorexia nervosa common?

Recently, specialized eating-disorder programs have seen a notable rise in patients in larger bodies seeking treatment. A 2022 review indicates that people in larger bodies comprise a substantial proportion of those admitted to inpatient medical stabilization units.

One review suggested that AAN might be more prevalent than low-weight anorexia, though AAN tends to be underrepresented in some clinical settings.

Researchers who examined 58 studies of consecutive referrals and admissions to eating disorder clinics found that in about 71% of those studies, individuals with AAN made up at least 10% of those seeking treatment.

The review also noted that some treatment centers reported sharp increases in AAN cases during certain periods. For example, one study documented more than a fivefold rise in adolescent AAN cases over six years.

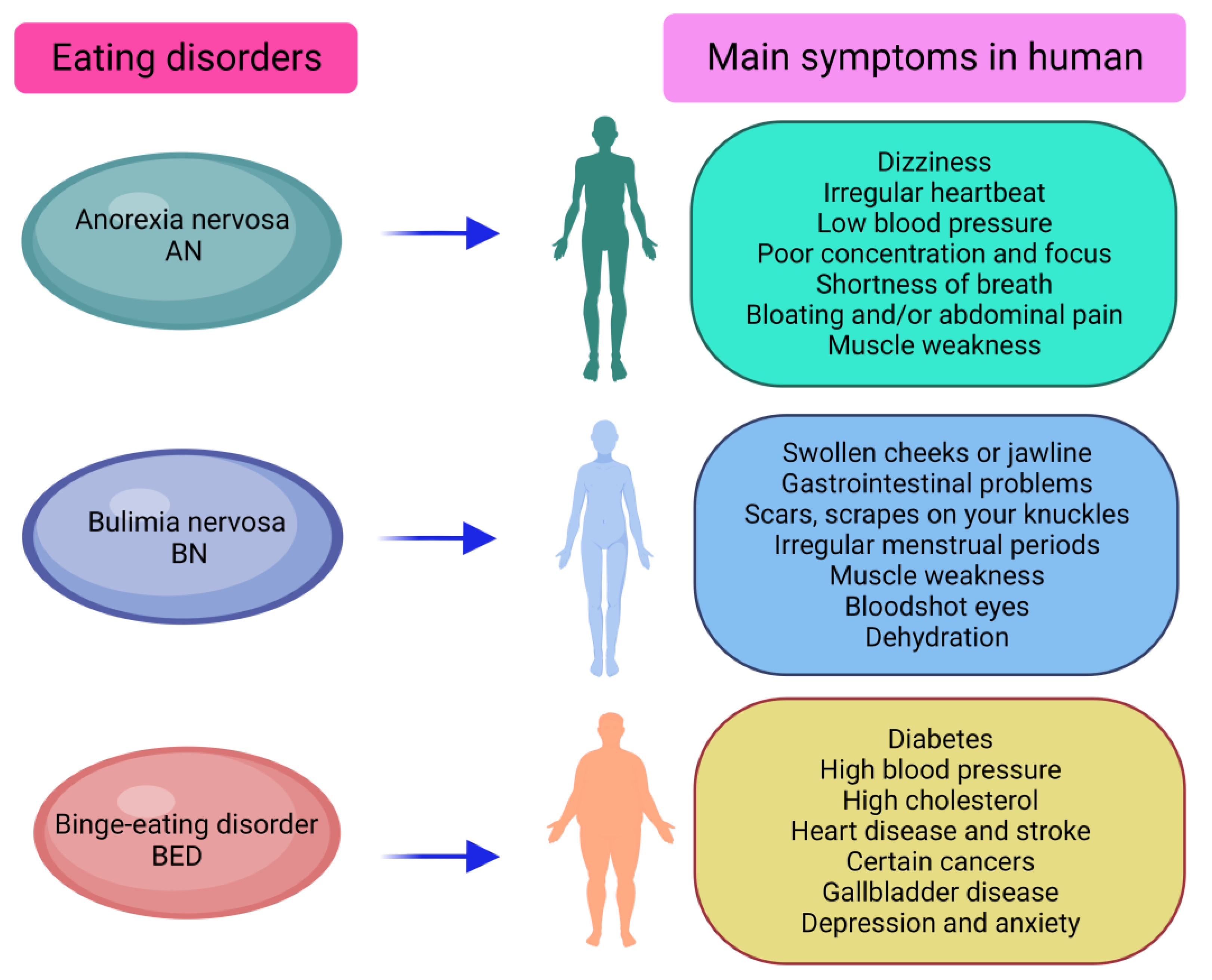

Atypical anorexia nervosa symptoms

Frequent signs of AAN include:

- Significant weight loss: Potentially dangerous reductions in weight from restrictive eating, fasting, excessive exercise, purging, laxative misuse, or other behaviors, even while staying within or above a “normal” weight bracket

- Fear of weight gain: Persistent worry about body weight and shape and an intense fear of becoming fat

- Restrictive eating patterns: Severe dieting, avoiding specific foods, or limiting overall food intake

- Body image disturbance: A distorted or inaccurate perception of one’s body shape or weight

- Physical health issues: Symptoms such as fatigue, lightheadedness, fainting, hair thinning, digestive troubles, irregular menstruation, and sensitivity to cold

- Psychological and emotional changes: Heightened anxiety, mood instability, irritability, withdrawal from social situations, and obsessive thoughts about food, dieting, and body image

What causes atypical anorexia nervosa?

As with other eating disorders, AAN likely arises from a mix of contributors:

- Genetics: A family history of eating disorders can raise the likelihood of developing one. Older studies indicate that female relatives of people with anorexia may be about 11 times more likely to develop AN compared with relatives of people without the disorder.

- Psychological and emotional traits: Certain personality characteristics, such as perfectionism, impulsivity, and high neuroticism, are commonly linked to eating disorders and often coexist with lower self-directedness, assertiveness, and cooperativeness.

- Sociocultural pressures: Cultural emphasis on thinness, societal standards, and media portrayals of the “ideal” body can strongly influence body dissatisfaction and contribute to disordered eating behaviors. One study examining peer pressure effects in Jordan reported that 31.6% of adolescents exhibited disordered eating behaviors.

- Traumatic experiences: Trauma can precipitate an eating disorder in susceptible individuals. Research has linked sexual interpersonal trauma with increased rates of anorexia and binge-eating disorder.

- Sports and athletics: Competitive sports can elevate risk for eating disorders. Restrictive diets and excessive exercise may arise from pursuing an ideal athletic physique or peak performance, and some athletes may continue intense exercise despite injury to maintain shape.

Potential health complications from AAN

AAN can produce many of the same health complications seen in classic AN, including:

- Nutritional deficiencies: Limited food intake may cause shortages of essential vitamins and minerals, producing weakness, fatigue, and other health problems.

- Electrolyte imbalances: Severe dietary restriction can disturb electrolyte levels, which may result in irregular heartbeat, weakness, and in extreme cases, cardiac issues.

- Gastrointestinal problems: Long-term restriction often leads to digestive complaints such as constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain.

- Hormonal disruptions: AAN can upset hormone balance and commonly affects menstrual cycles, causing irregularity or amenorrhea in females.

- Bone density loss: Poor nutrition and hormonal changes can reduce bone density, raising the risk of fractures and osteoporosis.

- Cardiovascular complications: Severe malnutrition can harm heart function, leading to low blood pressure, fainting, and other cardiac-related problems.

- Mental health consequences: AAN can exacerbate or precipitate conditions like anxiety, depression, and social isolation due to persistent preoccupation with food and body image.

Treatment for atypical anorexia nervosa

Care for AAN usually requires a multidisciplinary plan customized to the individual. Treatment may include:

- Medical oversight: Ongoing medical evaluations and monitoring of vitals, electrolyte levels, and overall health are crucial, particularly when physical complications are present.

- Nutritional therapy: A registered dietitian can assist in re-establishing balanced eating habits, restoring nutrition, and addressing fears or restrictions around food.

- Psychotherapy: Therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and group therapy can help address the psychological drivers, body-image issues, and disordered eating behaviors.

- Medication: When co-occurring mental health conditions are present, antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications may be used. Evidence for medication specifically treating anorexia remains limited.

- Family involvement: Family-based therapy or support can be especially helpful for adolescents or when family dynamics play a role in the disorder.

- Education and support groups: Joining support groups or psychoeducational programs can provide connection with others facing similar struggles and offer practical coping strategies.

Bottom line

Atypical anorexia nervosa challenges the common stereotype of anorexia by occurring in people who do not have very low body weight or BMI. Even so, it can be just as serious—and sometimes more severe—than low-weight anorexia.

If you think you might have atypical anorexia, reach out to a healthcare professional or an eating-disorder specialist. They can assess your condition, recommend appropriate treatment, and link you to resources and support.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.