Imagine your heart as a house with four doors. Each door (valve) should shut tightly after a guest (blood) comes in, so nothing sneaks back out. When one of those doors doesn’t close properly, blood leaks backward – that’s what doctors call valvular regurgitation. Most leaks are tiny and harmless, but when they grow, they can make your heart work overtime, leading to fatigue, shortness of breath, and sometimes the need for medication or surgery.

What Is Valvular Regurgitation

At its core, valvular regurgitation is “leaking” of a heart valve. The leaflets (or cusps) of a valve fail to seal fully, allowing blood to flow in the opposite direction during the cardiac cycle. This back‑flow forces the heart to pump extra volume to keep circulation adequate, which over time can strain the muscle and the lungs.

There are two main ways a valve can betray you:

- Regurgitation – the valve leaks.

- Stenosis – the valve narrows, limiting forward flow.

Both conditions cause murmurs, but the sound and timing differ. Below is a quick side‑by‑side look:

| Feature | Regurgitation | Stenosis |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of flow | Back‑ward (leak) | Forward (restricted) |

| Typical murmur | Holosystolic (continuous) | Mid‑systolic ejection |

| Common causes | Valve prolapse, infection, high pressure | Calcification, congenital narrowing |

Types of Valve Leakage

Mitral Regurgitation (MR)

The mitral valve sits between the left atrium and left ventricle. When it leaks, blood rushes back into the atrium every time the ventricle contracts. MR can be primary (the valve itself is damaged – think prolapse or calcium buildup) or secondary (the ventricle weakens from another disease, pulling the leaflets apart). According to CHAM, chronic MR may linger for years with barely any symptoms, while acute MR (often after a heart attack) shows up suddenly with severe breathlessness and a fainting feeling.

Typical MR symptoms

- Easy fatigue, especially after climbing stairs

- Shortness of breath during light activity

- A new or changing heart murmur heard by a doctor

- Occasional swelling of ankles (in advanced cases)

Aortic Regurgitation (AR)

The aortic valve is the heart’s main exit door, sending oxygen‑rich blood into the aorta. When it doesn’t close tight, blood dribbles back into the left ventricle during relaxation. This double‑filling spikes the left‑ventricular volume and creates a characteristic “wide pulse pressure” – high systolic pressure paired with a low diastolic pressure. The CV Physiology site illustrates how this extra volume amplifies the Frank‑Starling mechanism, initially boosting stroke volume but eventually overworking the heart.

Common AR causes

- Congenital bicuspid aortic valve (two leaflets instead of three)

- Damage from endocarditis (infection of the valve)

- Long‑standing high blood pressure stretching the aorta

- Connective‑tissue disorders like Marfan syndrome

Pulmonary & Tricuspid Regurgitation

These are the “right‑side” valves. Pulmonary regurgitation usually follows pulmonary hypertension, while tricuspid regurgitation often results from a dilated right ventricle due to left‑side failure or chronic lung disease. They’re less common but can still cause swelling in the abdomen or legs.

How Doctors Diagnose It

Listening Carefully – The Murmur

During a routine exam, a trained clinician can hear the tell‑tale “whoosh” of a regurgitant jet. The timing (systolic vs. diastolic) and intensity give clues about which valve is leaking.

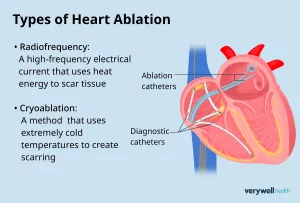

Imaging Toolbox

Echocardiography is the gold standard. A tiny probe on your chest creates live movies of blood flow. Color Doppler shows the direction of the jet, and the machine can calculate the regurgitant fraction – the percentage of blood that leaks back each beat. The American Heart Association notes that this non‑invasive test can be repeated over years to track disease progression.

When echo images are blurry, doctors may turn to Cardiac MRI or CT for a 3‑D view, especially to assess the aorta’s size in AR.

Other Tests

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – checks rhythm and any strain patterns.

- BNP blood test – rises when the heart is struggling.

- Stress testing – reveals how the valve behaves during exercise.

When Treatment Is Needed

Severity Grading

Doctors classify regurgitation as mild, moderate, or severe based on jet size, regurgitant fraction, and the effect on chamber size. Mild leaks often need only observation; severe leaks usually call for intervention.

Medical Management

Medications can’t close the door, but they can reduce the workload:

- Blood‑pressure reducers (ACE inhibitors, ARBs) lower the force pushing blood back.

- Diuretics help relieve fluid buildup in the lungs or legs.

- Anticoagulants may be needed if the patient has atrial fibrillation, a common companion to MR.

Lifestyle tweaks – a low‑salt diet, gentle aerobic activity, and regular weight checks – also help keep the heart from over‑exerting.

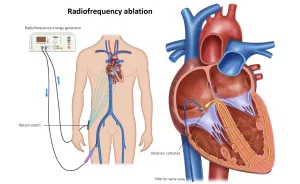

Interventional Options

When the leak is severe or symptoms appear, surgery or catheter‑based approaches are considered.

- Valve repair – stitching or reshaping the existing leaflets (often preferred for MR because it preserves native tissue).

- Valve replacement – inserting a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve. Mechanical valves last longer but require lifelong blood thinners; bioprosthetic ones avoid blood thinners but may wear out after 10‑15 years.

- Transcatheter therapies – less invasive. For AR, TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) is becoming common; for MR, the MitraClip device clips the leaflets together.

Choosing between repair and replacement is a joint decision between you, your cardiologist, and the heart‑valve team. They weigh factors like age, valve anatomy, and lifestyle.

Living With the Condition

Monitoring Schedule

Even a “mild” leak deserves regular follow‑up. Most guidelines suggest an echo every 1‑2 years for mild regurgitation, every 6‑12 months for moderate, and more frequent monitoring if the heart chambers start to enlarge.

Red‑Flag Symptoms

If any of these pop up, call your doctor promptly:

- Sudden, worsening shortness of breath (especially at rest)

- Chest pain or pressure

- Light‑headedness or fainting spells

- New or rapidly increasing swelling in ankles, feet, or abdomen

Patient Story

John, a 58‑year‑old accountant, was told he had “moderate mitral regurgitation” during a routine check‑up. He felt fine, but his echo showed his left atrium slowly enlarging. Instead of waiting, John chose a minimally invasive MitraClip procedure. Within weeks he felt more energetic, and his follow‑up echo showed the leak reduced from moderate to mild. “I thought surgery meant a long hospital stay and weeks of being out of work,” John told me, “but the quick‑clip approach let me get back to the spreadsheet—and the soccer field—so fast.” Stories like John’s illustrate why early, informed decisions can make a huge difference.

Expert Resources & Tips

When you’re hunting for trustworthy information, stick to reputable sources. The American Heart Association, Merck Manual’s video overview, and peer‑reviewed cardiology journals provide evidence‑based guidance without the drama of click‑bait.

If possible, ask your cardiologist to explain the regurgitant fraction and the size of the affected chamber in plain language. Understanding numbers like “regurgitant fraction = 38 %” or “left‑ventricular end‑diastolic volume = 180 mL” can seem daunting, but they’re the compass that tells the team whether to watch, medicate, or intervene.

Finally, remember you’re not alone. Support groups—both in‑person and online—offer a space to share tips, ask questions, and celebrate milestones (like a successful valve repair). Peer stories often fill the gaps that textbooks leave.

Conclusion

Valvular regurgitation is a common part of heart‑valve disease, ranging from harmless whispers to serious alarms. Knowing the basics—what the leak looks like, how it’s diagnosed, and when treatment becomes essential—puts you in the driver’s seat of your own health. Keep an eye on any new symptoms, stay on schedule with your echo appointments, and don’t hesitate to ask your care team for clarification whenever something feels fuzzy.

We’ve covered the anatomy, the types (mitral, aortic, pulmonary, tricuspid), how doctors spot the problem, the medical and procedural options, and what day‑to‑day life can look like. If you’ve learned something new, feel free to share it with a friend who might be dealing with “valve leakage symptoms.” And remember: a heart that leaks can still beat strong—with the right knowledge, support, and timely care.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.