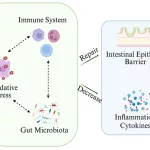

Quick answer: Yes, the pesticides on the fruits and veggies you eat can reach the trillions of microbes living in your gut, shaking up their balance, changing the chemicals they make, and sometimes nudging you toward inflammation or other health problems. At the same time, some friendly bacteria can actually break down these chemicals, and smart food choices plus a little probiotic help can keep the ecosystem humming.

Gut Matters

Before we dive into the science, let’s get on the same page about what the gut microbiome is. Think of it as a bustling city of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that live inside your intestines. This city does everything from digesting fiber to training your immune system and even chatting with your brain through chemical messengers.

When the city is thriving, you feel energetic, your digestion is smooth, and your mood is steadier. But when something intrusive – like a pesticide – barges in, it can knock down the “good” neighborhoods, let the “bad” ones expand, and mess with the city’s power grid (the metabolic pathways).

Researchers have pointed out that the gut microbiome acts as a “non‑target” organ for many environmental chemicals. According to a 2023 review in Gut Microbes, pesticide residues can directly damage bacterial membranes and alter gene expression, leading to loss of diversity and functional shifts a study. In short, the microbes we rely on for health are unintentionally caught in the crossfire.

What Research Shows

Let’s unpack the evidence. Below is a snapshot of the most compelling findings from the past few years.

| Study | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Sharma et al., 2023 | Pesticides reduced bacterial diversity by 12‑18% in mice | Lower diversity is linked to metabolic disorders. |

| Matsuzaki et al., 2023 | Altered gut‑brain axis signaling after chronic exposure | Potential link to anxiety, depression, and neurodegeneration. |

| Zhang et al., 2024 (observational) | Long‑term organophosphate exposure associated with loss of Bacteroides | Changes in short‑chain fatty‑acid production. |

| Ohio State “atlas”, 2025 | Mapped 306 pesticide‑bacteria interactions; identified one strain that mitigates inflammation | Hints for probiotic interventions. |

One of the most eye‑opening analyses pooled 117 studies and concluded that “eating pesticides can disrupt your gut microbiome” – a statement that shows up in headlines and scientific abstracts alike. The take‑away? Even low, everyday levels aren’t completely harmless to the microscopic world inside you.

If you’re curious about the nitty‑gritty details of how these chemicals get into our gut, check out the pesticides gut bacteria post for a step‑by‑step breakdown.

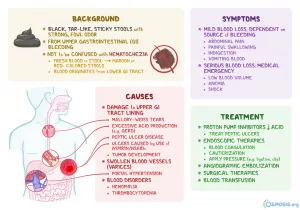

How Pesticides Act

There isn’t just one way these chemicals mess with your microbiome. Here are the main mechanisms that researchers keep talking about:

Direct antimicrobial action

Many pesticides are designed to kill insects, and their modes of action – membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, DNA damage – can also affect bacterial cells. For instance, chlorpyrifos has been shown to pierce the outer membrane of Clostridium species, reducing their numbers dramatically.

Metabolic interference

Some pesticides act like alternative fuels. Gut bacteria may start metabolizing them instead of the fiber you eat, which shunts the production of short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate. SCFAs are the “fuel” for colon cells and play a huge role in immune regulation. When their production drops, inflammation can creep in.

Immune modulation

Changes in the microbial community can increase gut permeability – the “leaky gut” phenomenon. This lets bacterial fragments into the bloodstream, triggering an immune response. A 2023 paper on the microbiota‑gut‑brain axis showed that pesticide‑induced permeability amplified neuroinflammatory markers a study.

Selection for resistant strains

Just like how some weeds become resistant to herbicides, some bacteria develop resistance to pesticides. These resistant strains often belong to the Enterobacteriaceae family, which includes opportunistic pathogens. Their overgrowth can predispose you to infections.

Biodegradation by friendly microbes

Not all news is bleak. The Ohio State “atlas” discovered several gut bacteria that actually degrade pesticide molecules, turning them into harmless by‑products. One such strain, a member of the Lactobacillus genus, reduced inflammation in mouse models.

Practical Steps

So, what can you do to protect your gut city while still enjoying a varied diet? Below are friendly, doable actions.

Choose low‑pesticide produce

When possible, shop the organic aisle or rinse conventional produce thoroughly. A quick 10‑minute soak in a 1% vinegar solution can slash surface residues by up to 80%.

Embrace targeted probiotics

Some probiotic strains have shown pesticide‑degrading abilities. Look for products that list Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium longum. Our own deep‑dive on probiotics pesticides gives a handy starter list.

Feed the good guys

Prebiotic fibers such as inulin, resistant starch, and chicory root act as food for beneficial microbes. Adding a handful of cooked beans, a spoonful of ground flaxseed, or a serving of Jerusalem artichoke each day gives them a boost.

Stay hydrated and antioxidant‑rich

Water helps flush out chemicals, while foods rich in polyphenols (berries, green tea, dark chocolate) support the gut’s detox enzymes. Think of it as giving your microbial city a fresh water supply and a clean energy grid.

Consider testing if you’re concerned

If you live near heavy agricultural zones or notice persistent digestive upset, you can order a stool microbiome analysis from a certified lab. It will tell you which bacterial groups are flourishing—or fleeing.

Talk to a specialist

When in doubt, a gastroenterologist or a registered dietitian with a focus on microbiome health can craft a personalized plan. Their guidance is especially valuable if you have chronic conditions like IBS or autoimmune disease.

Balancing View

It’s easy to paint pesticides as villains, but the picture is more nuanced. Pesticides have boosted global food production, helped keep us safe from crop‑destroying pests, and reduced the need for manual labor. Those benefits matter, especially for feeding a growing population.

What we’re calling attention to is the hidden cost to our inner ecosystems. By acknowledging the trade‑off, we can push for smarter regulation, promote integrated pest management, and support research into “micro‑friendly” chemicals. In other words, we can enjoy abundant food without silently compromising the tiny allies that keep us healthy.

For a deeper look at how everyday chemicals interact with gut health, see our article on gut health chemicals. It explores everything from food additives to cleaning agents—and how they shape the microbial metropolis.

References

Sharma, T., Natesh, N. S., Pothuraju, R., & Batra, S. K. (2023). Gut microbiota: a non‑target victim of pesticide‑induced toxicity. Gut Microbes, 15(1). Link

Matsuzaki, R., Gunnigle, E., Geissen, V., et al. (2023). Pesticide exposure and the microbiota‑gut‑brain axis. ISME Journal, 17(8), 1153‑1166. Link

Zhang, K., Paul, K., Jacobs, J. P., et al. (2024). Ambient long‑term exposure to organophosphorus pesticides and the human gut microbiome. Environmental Health, 23, 41. Link

Gama, J., Neves, B., & Pereira, A. (2022). Chronic effects of dietary pesticides on the gut microbiome and neurodevelopment. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 931440. Link

Zhu, J., Chen, L., et al. (2025). How gut bacteria change after exposure to pesticides. Nature Communications. Link

For more practical tools, explore the internal resources linked throughout this post. Your gut microbiome is a resilient community—give it the support it needs, and it will keep you feeling balanced, vibrant, and ready for whatever the day brings.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.