Okay, let’s get straight to the point. A papilloma is a tiny, wart‑like bump that shows up when certain viruses—or sometimes just a bit of irritation—make the skin’s surface cells grow outwards. Most of the time they’re harmless, but the “why did this happen to me?” and “what should I do about it?” questions can feel pretty unsettling. Below you’ll find a friendly, down‑to‑earth guide that explains the causes, the symptoms you might notice, and the safe, doctor‑approved ways to treat or prevent them. Ready? Let’s dive in.

Understanding Papilloma

What does “papilloma” actually mean?

Think of a papilloma as a little mushroom that grows from the skin’s outer layer (the epithelium). Inside, there’s a fibro‑vascular core—basically a tiny bundle of blood vessels—wrapped in a smooth layer of cells. This structure is what doctors see under the microscope when they confirm that a bump is a papilloma rather than something more serious.According to the National Institutes of Health, the hallmark is a benign, outward‑facing growth that rarely becomes cancerous.

Are papillomas the same as warts?

They’re cousins, not twins. Both are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), but “wart” usually refers to the more common skin‑type lesions caused by a broader mix of HPV strains. Papillomas tend to be smoother, sometimes called “skin growths,” and they often appear in places where the skin rubs against something else—think armpits, neck, or even the lining of the mouth.Verywell Health explains that low‑risk HPV types (6 and 11) are the typical culprits.

Where can they show up?

Practically anywhere there’s epithelial tissue:

- Skin (hands, neck, armpits, chest folds)

- Oral cavity and throat

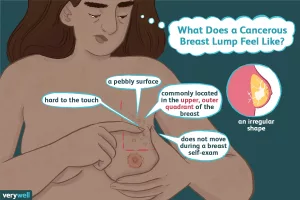

- Breast ducts (intraductal papilloma)

- Genital area

- Respiratory tract (voice box, sinuses)

- Even the eye’s conjunctiva (rare)

Each location can bring its own set of quirks, which we’ll explore later.

Should I be worried?

In the vast majority of cases, a papilloma is completely benign. It won’t spread, and it rarely turns malignant. That said, a few edge cases—like a squamous‑cell papilloma in the lung—can transform, but the odds are minuscule. A study on pulmonary papilloma notes that malignant change is “rare” and usually linked to long‑standing squamous lesions.

What Causes Papilloma

Human papillomavirus (HPV) – the main suspect

HPV is the heavyweight champion behind most papillomas. Low‑risk strains—especially types 6 and 11—prefer to stay in the superficial layers of skin and mucous membranes, causing these gentle outgrowths. After exposure, it can take about three months for a bump to appear, but the virus can hide in the skin for years before deciding to surface.StatPearls notes that the incubation period varies widely, which explains why a friend’s “just‑got‑vaccinated” story may not prevent a bump that shows up later.

Non‑viral triggers

Not every papilloma loves a viral party. Rarely, they arise from chronic irritation or trauma—think repeatedly rubbing a skin fold or a small cut that never quite heals. Hormonal fluctuations (pregnancy, menopause) can also nudge the skin into forming these bumps. Even an overactive immune system can misfire, leading to what dermatologists call “inverted papillomas” in places like the urinary tract.

Risk factors that increase your odds

- Obesity – More skin folds mean more friction and moisture, perfect for HPV to set up camp.

- Diabetes – High blood sugar can weaken immunity, letting the virus linger.

- Immunosuppression – Whether from medication, illness, or age, a weaker defense tilts the scales.

- Hormonal changes – Pregnancy, menopause, or thyroid disorders can tip the hormonal balance.

- Genetics – Some families seem to inherit a “skin‑sensitivity” trait.

These aren’t guarantees, just clues that help doctors decide why a particular bump popped up.

How does HPV actually get to your skin?

HPV travels like a sneaky houseguest. It can be passed through direct skin‑to‑skin contact (yes, even a handshake can do it if there’s a tiny cut), via contaminated objects—known as fomites—like towels, razors, or gym equipment, and, of course, through sexual contact. The virus is also capable of vertical transmission from mother to baby during birth, which is why newborns sometimes show tiny oral papillomas.

Spotting Symptoms

Typical signs you might notice

Most papillomas are painless, smooth, and range from a pinpoint dot to a pea‑size bump. They might itch if they’re in a friction zone, and if you accidentally brush against them, they can bleed a little—nothing dramatic, but enough to make you wonder.

Papilloma pictures (what to look for)

Imagine a tiny mushroom cap or a translucent, flesh‑colored nodule. On the skin, they often appear as a single, well‑defined, raised lesion. In the mouth, they look like a soft, pinkish bump on the inner cheek or palate. If you search “papilloma pictures” you’ll see the variety of shapes, but the common thread is that they’re generally smooth and non‑ulcerated.

When to be extra cautious

- Rapid growth within weeks

- Persistent pain, ulceration, or foul odor

- Color change (darkening, redness spreading outward)

- Difficulty breathing when the bump is in the airway

- Unexplained bleeding or discharge (e.g., from a breast papilloma)

If any of these pop up, it’s time to schedule a visit with a dermatologist or the appropriate specialist.

Quick self‑check checklist

- Is the bump < 5 mm? Likely benign.

- Is it smooth, not crusty? Good sign.

- Has it stayed the same for several weeks? Probably harmless.

- Any pain when touched? Consider a consult.

How It’s Diagnosed

Physical exam and dermoscopy

Your doctor will first look at the bump with the naked eye and may use a dermoscope—a magnifying tool that reveals patterns in the skin’s surface. Certain vascular patterns hint at a papilloma, while irregular streaks may raise red flags.

Biopsy – the gold standard

If the lesion looks atypical, the clinician will take a tiny tissue sample. Under a microscope, pathologists can confirm the fibro‑vascular core and rule out carcinoma. According to NIH’s description, a biopsy is the definitive way to differentiate a papilloma from a more dangerous growth.

Imaging for deeper spots

When papillomas hide inside the lung, sinuses, or breast ducts, doctors turn to CT, MRI, or ultrasound. A pulmonary papilloma, for instance, is usually visualized on a chest CT and then confirmed with a small tissue excision.The NCBI article emphasizes that imaging helps plan the surgical approach.

Lab work – when it helps

In some cases (especially recurrent or widespread lesions), the doctor may order an HPV DNA test to identify the strain. For patients with diabetes or immune disorders, a basic blood panel can gauge overall health before an invasive procedure.

Treatment Options

When is treatment really needed?

Most papillomas are left alone unless they:

- Cause pain, itching, or bleeding

- Appear in a cosmetically sensitive area (face, neck)

- Obstruct a functional space (airway, breast duct)

- Show suspicious changes that need removal for certainty

Surgical excision

Cutting the bump out with a scalpel is the classic approach. It’s quick, ensures complete removal, and allows the pathologist to examine the tissue. Recovery is usually a week of mild soreness, and the scar can be minimized with proper suturing.

Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen)

Freezing the lesion causes the cells to die and slough off. It’s an office‑based procedure, often done in one or two sessions. The downside? A white “ice” spot may linger for a few weeks, and there’s a faint chance of hypopigmentation.

Laser therapy

CO₂ or erbium lasers vaporize the growth with precision, making it ideal for facial papillomas where you want minimal scarring. Recovery is swift, but the equipment cost can make it pricier.

Electrosurgery & cautery

Using electric current to burn away the bump works well for small, accessible lesions. It’s similar to laser in outcome but generally more affordable.

Topical agents

Prescription creams like imiquimod or podofilox stimulate the immune system to attack the virus from the outside. For respiratory papillomatosis, cidofovir (an antiviral) has been used off‑label with some success.The pulmonary papilloma source mentions cidofovir as a medication option when surgery isn’t feasible.

Alternative/minimally‑invasive tricks

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) combines a light‑sensitive drug with a specific wavelength of light to destroy the lesion. Chemical keratolytics (salicylic acid, trichloroacetic acid) can also dissolve superficial papillomas, though they’re more common for warts.

Managing underlying factors

If obesity or diabetes is part of the story, weight‑loss programs or better blood‑sugar control can reduce future outbreaks. And—yes—HPV vaccination (Gardasil 9) protects against the strains that cause most skin papillomas, so talk to your healthcare provider about getting the shot.

Comparing treatment modalities

| Method | Setting | Typical Sessions | Pain Level | Scarring? | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryotherapy | Office | 1‑2 | Mild | Minimal | $$ |

| Laser | Clinic | 1 | Moderate | Low | $$$ |

| Surgical excision | OR (if large) | 1 | Moderate‑high | Variable | $$$ |

| Topical imiquimod | Home | 4‑8 weeks | Burning/itch | None | $ |

*Cost tiers are illustrative; actual prices vary by region and insurance coverage.

Preventing Recurrence

Vaccinate against HPV

Gardasil 9 shields you from the nine most common HPV types, including the low‑risk strains that cause skin papillomas. Even if you’ve already had a bump, the vaccine can stop future infections. CDC’s vaccine page recommends it for both males and females up to age 45.

Skin hygiene and protection

Keep the areas prone to friction clean and dry. Use gentle cleansers, avoid excessive scratching, and consider breathable fabrics in hot weather to reduce moisture buildup.

Boost your immune system

- Balanced diet rich in vitamins A, C, E, and zinc

- Regular moderate exercise

- 7‑9 hours of sleep per night

- Stress‑management techniques (meditation, hobbies)

These habits are especially important for diabetics and those with obesity, as they directly influence how well your body can keep HPV in check.

Regular check‑ups

If you have a history of papillomas, schedule an annual skin exam with a dermatologist. Early detection of any new growth makes removal easier and less invasive.

Conclusion

Papillomas are mostly harmless, wart‑like bumps that appear when low‑risk HPV or other irritants convince your skin to grow a little mushroom. While the majority never cause trouble, it’s completely understandable to be curious—or even worried—when a new lump shows up. By knowing the common causes (HPV, friction, hormonal shifts), recognizing the typical symptoms, and understanding the range of safe treatment options—from simple cryotherapy to precise laser removal—you’re equipped to make confident decisions about your health.

Remember, balance is key: the benefits of treatment (pain relief, cosmetic improvement) should be weighed against the natural, benign nature of most papillomas. If you spot a new bump, start with a gentle self‑check, then reach out to a qualified dermatologist for an expert opinion. And don’t forget: a healthy lifestyle, good hygiene, and the HPV vaccine are your best allies in keeping future papillomas at bay.

What’s your experience with skin bumps? Have you tried a particular treatment that worked well? Share your story in the comments below, or ask any lingering questions—you’re not alone on this journey.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.