Short answer: polycythemia vera isn’t hereditary. It’s an acquired blood‑cancer driven by a somatic mutation—most often in the JAK2 gene—that pops up after you’re born. That doesn’t mean the story ends there, though. Because the condition can look a lot like a truly inherited form of erythrocytosis, many families wonder if it runs in the genes. In this article we’ll unpack the science, compare the hereditary cousins, and give you a clear roadmap for testing, treatment, and peace of mind.

Causes Explained

Which Gene Mutations Drive Polycythemia Vera?

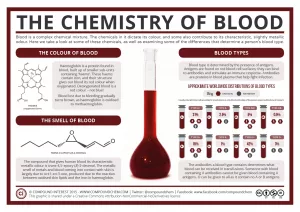

The hallmark of polycythemia vera (PV) is a mutation that tells the bone marrow to crank out red blood cells (and often white cells and platelets) like a factory on overdrive. The most common “driver” is the JAK2 V617F mutation—found in about 90 % of cases. A smaller slice (2‑5 %) carries mutations in JAK2 exon 12, while a handful of patients also harbor alterations in TET2, ASXL1, or other myeloid‑associated genes.

These changes are somatic, meaning they arise in a single hematopoietic stem cell after conception. They are not present in every cell of the body and, crucially, they are not passed from parent to child.

Acquired vs. Inherited – Key Definitions

- Acquired (somatic) mutation: appears during a person’s life, often without a clear trigger. The mutation lives only in the blood‑forming cells that carry it.

- Inherited (germline) mutation: is baked into each cell from conception and can be handed down through families.

Polycythemia vera falls squarely in the first bucket. According to NCBI MedGen, “Modes of inheritance: Not genetically inherited.”

Table 1. Acquired vs. Inherited Blood Disorders

| Disorder | Inheritance | Typical Gene | Is It PV? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycythemia vera | Not inherited | JAK2 (somatic) | ✓ |

| Familial erythrocytosis (ECYT1) | Autosomal dominant | EPOR, SH2B3, JAK2 (germline) | ✗ |

| Congenital polycythemia | Autosomal recessive/dominant | VHL, EGLN1, others | ✗ |

Hereditary vs. Acquired

Genetic Heritability (“hereditary risk polycythemia”)

If you’ve traced a family line where several relatives have an unusually high red‑cell count, you might be looking at familial erythrocytosis. Unlike PV, this condition is truly inherited—most often an autosomal‑dominant mutation in the EPOR receptor, SH2B3, or even a germline JAK2 alteration. The OMIM entry for familial erythrocytosis (ECYT1) spells out the autosomal‑dominant inheritance pattern and links it to chromosome 19p13.21 (see OMIM #133100).

Clinical Overlap & Distinguishing Features

Both conditions produce a surplus of red blood cells, but the “experience” is often different. Polycythemia vera usually brings:

- Pruritus after a warm shower (the “itchy‑after‑bath” hallmark)

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly)

- Thrombosis‑related complications (deep‑vein clot, stroke risk)

- Elevated platelets and white‑cell counts

Hereditary erythrocytosis typically presents with a “quiet” excess of red cells—no itching, no splenomegaly, and fewer clotting issues. Symptoms, when they appear, are often limited to mild headache or fatigue.

When to Suspect a Hereditary Form

- Onset before age 30 – PV rarely shows up that early.

- Multiple first‑degree relatives with isolated erythrocytosis.

- Negative JAK2 V617F test.

- No obvious secondary cause (smoking, altitude, lung disease).

Risk Factors

Age & Sex Trends (Polycythemia Vera Causes)

Polycythemia vera most often appears in the sixth decade of life, with men about 1.5 times more frequently diagnosed than women. The reasons for this gender skew are still under investigation, but the data are solid: MedlinePlus notes a prevalence of roughly 44‑57 per 100 000 in the United States.

Environmental & Lifestyle “Triggers” (Not Hereditary)

- Chronic smoking

- Living at high altitude

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Certain lung diseases that lower oxygen saturation

These factors cause “secondary polycythemia,” a different beast that’s driven by the body’s attempt to compensate for low oxygen. It’s important to rule out these possibilities before labeling anything as PV.

Symptoms Overview

Common PV Symptoms (Polycythemia Symptoms)

Even though many patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis, the classic “PV‑package” often includes:

- Persistent headache or dizziness

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- Itchy skin, especially after a warm bath or shower

- Facial redness (plethora)

- Blurred vision or visual disturbances

- Fatigue and general “brain fog”

Symptoms More Typical of Hereditary Erythrocytosis

Inherited forms usually lack the itching and spleen‑related fullness. You might notice a mild, “just a little too energetic” feeling, occasional headaches, or a subtle pale‑red complexion, but the severe hyperviscosity signs are rare.

Quick Checklist – Do You Recognize Any of These?

- [ ] Unexplained itching after a hot shower

- [ ] Persistent, unrelenting headache

- [ ] Enlarged spleen causing left‑upper‑abdominal fullness

- [ ] Unusual blood clots (deep‑vein thrombosis, stroke)

- [ ] Reddened face that doesn’t go away

If you tick a few boxes, it’s worth chatting with a hematologist. Even a single symptom can be a clue.

Diagnosis Path

Standard Work‑up

When a doctor suspects polycythemia, the first step is a thorough blood count (CBC). Elevated hemoglobin, hematocrit, and sometimes platelet counts raise the alarm. From there, the usual algorithm looks like this:

- Measure serum erythropoietin (EPO) – low in PV, normal or high in secondary polycythemia.

- Perform a JAK2 V617F PCR or next‑generation sequencing test – a positive result clinches the diagnosis.

- If JAK2 is negative but suspicion remains, test for exon 12 mutations or other less common PV‑associated genes.

- Bone‑marrow biopsy is rarely needed now, but it can confirm hypercellularity and rule out other myeloproliferative neoplasms.

When Is Germline Testing Useful?

Only if the family history points toward a hereditary erythrocytosis. In that scenario, a “germline panel” looking at EPOR, VHL, EGLN1, and related genes can save you months of uncertainty. It’s a subtle decision, so a genetics counselor or a hematology‑on‑call specialist is the right person to guide you.

Diagnostic Flowchart (placeholder for graphic)

Imagine a simple flowchart: Suspicion → CBC → EPO → JAK2 test → If negative & family history → Germline panel.

Treatment Options

Phlebotomy – The Classic First Step

Removing a unit of blood (about 500 ml) every week or fortnight reduces the hematocrit to a safer level (<45 % for men, <42 % for women). It's like draining excess water from a flooded basement—simple, inexpensive, and instantly effective.

Low‑Dose Aspirin – Clot Prevention with a Caveat

Most doctors prescribe 81 mg of aspirin daily to thin the blood’s clot‑forming tendency. The trade‑off is an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, especially in older patients, so the decision must be individualized.

Cytoreductive Drugs – When the Blood Won’t Calm Down

- Hydroxyurea: Reduces all three blood‑cell lines; first‑line for patients over 60 or those with high thrombotic risk.

- Interferon‑α: Considered for younger patients or those who want to avoid hydroxyurea’s long‑term side effects.

- Ruxolitinib (Jakafi): A JAK‑inhibitor used when hydroxyurea fails or isn’t tolerated.

Pros & Cons Table

| Therapy | Benefit | Potential Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Phlebotomy | Immediate reduction of blood thickness | Iron deficiency, fatigue |

| Low‑dose aspirin | Decreases clot formation | GI bleed, especially with NSAIDs |

| Hydroxyurea | Long‑term control of cell counts | Skin ulcers, potential leukemic transformation (rare) |

| Interferon‑α | Effective in younger patients, may improve molecular remission | Flu‑like symptoms, depression |

| Ruxolitinib | Targets JAK2 mutation directly, reduces spleen size | Infection risk, cost |

Bottom Line

In a nutshell, polycythemia vera is an acquired condition, not a hereditary one. Its root cause is a somatic JAK2 mutation that appears during life, so you won’t pass it on to your kids. If you do see multiple close relatives with an elevated red‑cell count, the likely culprit is a different, truly inherited disorder such as familial erythrocytosis, which involves genes like EPOR or SH2B3.

Understanding this distinction matters because it shapes the testing strategy (JAK2 assay vs. germline panel), guides treatment choices (phlebotomy and aspirin for PV, perhaps nothing for a benign hereditary form), and eases the anxiety of wondering “Did I get this from Mom?”

So, if you’ve just learned you have a high red‑cell count, take a breath. Talk to a board‑certified hematologist, get the JAK2 test, and discuss family history openly. The right answers will lead to the right care, and you’ll have the confidence that you’re tackling the right problem.

What’s your experience with blood‑count testing? Have you ever wondered whether a condition in your family might be hereditary? Drop a comment below or reach out to a qualified specialist—you don’t have to navigate this alone.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.