If a doctor has told you that a replacement heart valve is on the horizon, you’re probably feeling a mix of curiosity, worry, and a dash of “what‑now?” – and that’s completely normal. In the next few minutes we’ll walk through the basics, compare the options, and give you a realistic picture of what to expect, all while keeping the conversation as friendly as a chat over coffee.

Understanding Replacement Valves

First things first: what exactly is a replacement heart valve and why do we need one? Think of your heart as a well‑orchestrated concert hall. The valves are the doors that let the music (blood) flow in the right direction. When a door gets stuck or starts leaking, the whole performance suffers. A replacement valve simply steps in to take over that job, restoring smooth flow and preventing the dreaded symptoms of breathlessness, fatigue, or even heart failure.

Most people need a valve replacement because of severe stenosis (the door won’t open enough) or regurgitation (the door won’t close properly). Congenital heart defects, age‑related wear, or a failed previous valve can also trigger the need for a new one. Congenital heart defects are a common reason for younger patients to face this decision early in life.

Before any valve ever makes it to the operating table, it undergoes rigorous heart valve testing. Researchers follow strict FDA and EMA protocols, running the valve through pressure cycles that mimic decades of heartbeat activity. According to a new artificial heart valve study from the British Heart Foundation, newer polymer materials are now holding up far better than older designs, especially when it comes to calcification resistance.

Valve Types Overview

When it comes to replacement valves, the market essentially offers three families: mechanical (metal), bioprosthetic (tissue), and transcatheter (catheter‑delivered). Each family has its own personality, benefits, and trade‑offs.

| Valve Type | Key Features | Typical Longevity |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical (metal) | Durable carbon/titanium leaflets; requires lifelong anticoagulation | 20‑30 years (often a lifetime) |

| Bioprosthetic (tissue) | Animal or pericardial tissue; lower clot risk; may calcify | 10‑15 years (younger patients less) |

| Transcatheter (TAVI/TPV) | Delivered via catheter; minimally invasive; suited for high‑risk surgery patients | 12‑15 years (depends on device) |

Let’s dig deeper into the two most common surgical options – mechanical and bioprosthetic – before we explore the less invasive cat‑based solutions.

Mechanical Valve Benefits

Mechanical valves are the rock‑stars of durability. Made from carbon‑fiber or titanium, they can last a lifetime, which means fewer repeat surgeries. If you’re in your 40s or 50s and want to avoid a second operation, a mechanical valve might feel like the safe bet.

However, there’s a price to pay: the need for lifelong anticoagulation (usually warfarin). This blood‑thinner keeps clots at bay but demands regular INR checks and brings a slight bleeding risk. Imagine having to schedule a quick lab visit every few weeks – not glamorous, but manageable with a good support team.

Bioprosthetic Valve Benefits

Bioprosthetic valves, often called “tissue” valves, are crafted from bovine pericardium or porcine leaflets. They whisper quietly – no audible clicking, and they don’t demand blood thinners for most patients. That’s a huge relief for anyone who dislikes the idea of constant medication monitoring.

The trade‑off? They tend to calcify over time, especially in younger bodies where calcium metabolism is more aggressive. Expect a lifespan of roughly 10‑15 years, after which a redo surgery might be needed. For seniors, this often aligns perfectly with life expectancy, making tissue valves a popular choice.

Transcatheter Valve Options

If open‑heart surgery feels daunting, transcatheter methods—like Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) or Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve (TPV) therapy—offer a less invasive route. A thin catheter, guided through a vein, delivers the new valve right to the heart, almost like threading a tiny, life‑saving beaded necklace into place.

These approaches shine for patients deemed high‑risk for traditional surgery, or for those who simply want a quicker recovery. The Evolut™ Low‑Risk Trial showed impressive 4‑year outcomes, proving that TAVI isn’t just a fallback—it’s becoming a first‑line option for many.

Choosing the Right Valve for You

Now that you’ve met the main players, how do you pick the champion for your own heart?

- Age matters. Under 65? Doctors often lean toward mechanical valves for durability. Over 65? Tissue valves usually win the popularity vote because the lifespan matches typical life expectancy.

- Lifestyle matters. If you’re an avid cyclist or enjoy high‑intensity sports, a mechanical valve’s durability may be appealing, but you’ll need to be comfortable with regular blood‑thinner monitoring. If you prefer a “set it and forget it” vibe, tissue valves are quieter and lighter on medication.

- Medical conditions matter. Atrial fibrillation, kidney disease, or a history of bleeding can sway the decision toward tissue valves. Conversely, patients with a strong desire to avoid repeat surgery might accept the anticoagulation burden of a mechanical valve.

- Pregnancy and children. For women planning pregnancy, tissue valves are often recommended because anticoagulants can harm a developing baby. In pediatric cases, pediatric heart valve options are specially designed to grow with the child or be easily replaceable. Child cardiac surgery teams usually tailor a plan that balances growth potential and durability.

Every heart is unique, so your cardiology team will weigh these factors alongside imaging results, blood tests, and your personal preferences. Don’t hesitate to ask them why they recommend one valve over another—that’s how you become an active participant in your care.

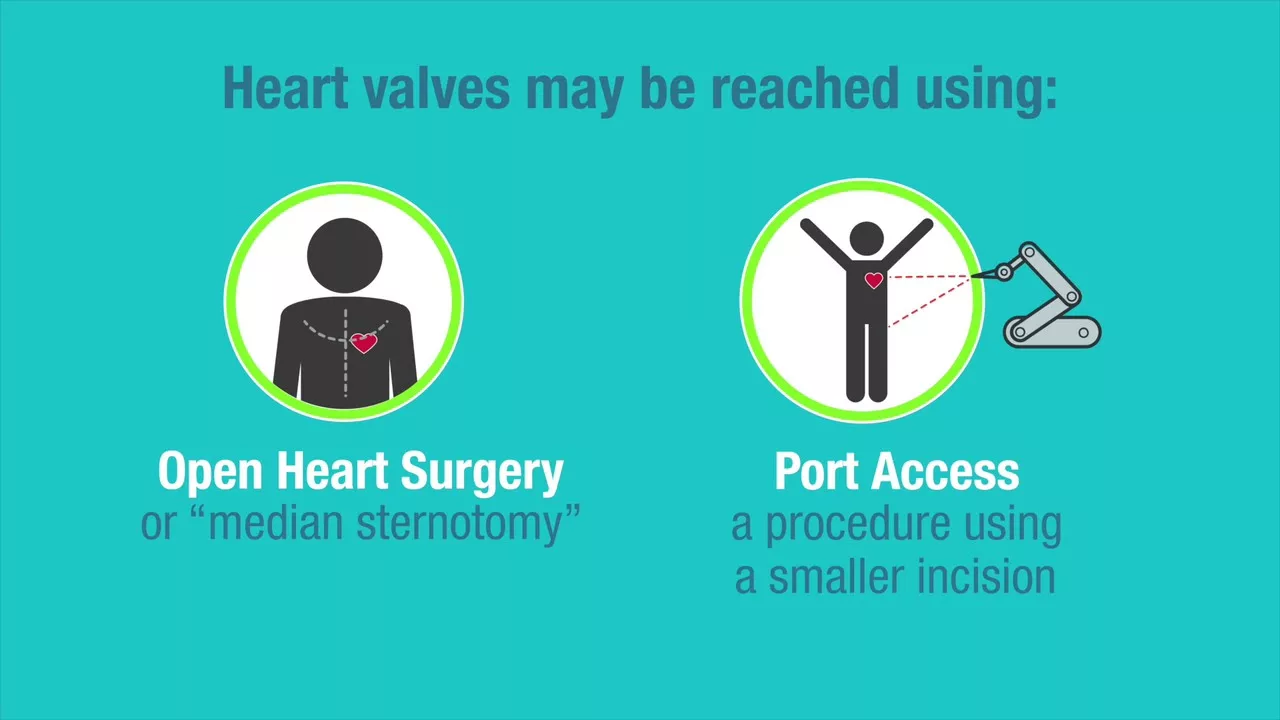

Procedure Options

Let’s peek behind the curtain of the two main surgical routes.

Open‑Heart Surgical Replacement (SAVR)

Surgeons make an incision through the chest, halt the heart with a heart‑lung machine, remove the diseased valve, and sew the new one into place. The procedure typically lasts 2‑4 hours, followed by a few days in the ICU and a hospital stay of about a week. Recovery can take 6‑12 weeks, during which you’ll gradually re‑introduce activity.

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI)

Through a tiny incision in the groin, a catheter slides up to the heart, expands the new valve, and locks it into place. No need for a heart‑lung machine, and most patients go home within 2‑3 days. The whole process feels more like a diagnostic procedure than a major surgery.

Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve (TPV) – Harmony™

The Harmony™ TPV is a pig‑tissue valve mounted on a wire frame, perfect for patients with pulmonary valve issues who want to delay another open‑heart operation. It’s a game‑changer for many, especially those who have already undergone multiple surgeries.

Whichever route your team chooses, the goal is the same: a valve that opens and closes smoothly, letting your heart pump confidently.

Benefits vs Risks – A Balanced View

| Aspect | Mechanical Valve | Bioprosthetic Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Longevity | 20‑30 years, often lifetime | 10‑15 years, may need re‑operation |

| Anticoagulation | Life‑long warfarin (bleeding risk) | Usually none (lower clot risk) |

| Noise | Can click (often unnoticed) | Silent |

| Calcification | Rare | Common, especially congenital or younger patients |

| Suitability for Pregnancy | Not ideal (anticoagulants) | Preferred |

Notice how each benefit is paired with a counter‑point? That’s intentional – you deserve the full picture. Mechanical valves give you peace of mind about durability, but you’ll be friendlier with your pharmacist. Tissue valves let you skip the daily pill, yet you may face a future surgery. Your decision hinges on which trade‑off feels more comfortable for your life.

Post‑Implant Care & Ongoing Testing

After the valve is in place, the real work begins: monitoring and caring for it.

- Imaging follow‑up. An echocardiogram at 3 months, then yearly, checks that the valve moves freely. These scans are part of routine heart valve testing and help catch any early signs of wear.

- Anticoagulation management. If you have a mechanical valve, your INR will need regular checks. Some newer oral anticoagulants (DOACs) aren’t approved for mechanical aortic valves, so stick with your doctor’s warfarin plan.

- Lifestyle tweaks. Light exercise is encouraged after the healing window. Avoid high‑impact sports if you have a mechanical valve on blood thinners, but a gentle bike ride or swimming can boost heart health.

- Signs of trouble. Shortness of breath, new chest pain, or unexplained fatigue should prompt a call to your cardiology team right away.

Think of your new valve as a trusted teammate. With regular check‑ins and a bit of self‑care, you’ll keep it performing like a well‑tuned instrument.

Future Innovations & Hopeful Horizons

Science never rests, and the field of valve replacement is buzzing with exciting breakthroughs.

Researchers like Professor Geoff Moggridge have unveiled polymer‑based artificial valves that resist calcification far better than traditional tissue valves (new artificial heart valve research). Imagine a valve that lasts a lifetime without the need for blood thinners – that’s the direction the industry is marching toward.

Another frontier is 3‑D printing. Custom‑made valves that match a patient’s exact anatomy are already being trialed, promising fewer complications and better fit. For children, this could mean a valve that grows with them, reducing the number of repeat surgeries dramatically.

Even gene‑editing technologies are peeking over the horizon, targeting the root causes of congenital valve malformations. While still early, these advances give hope that future generations may face fewer invasive procedures altogether.

Wrapping It All Up

Choosing a replacement heart valve isn’t just a medical decision; it’s a life decision. You’ve learned that mechanical valves offer durability at the cost of lifelong medication, while tissue valves trade some longevity for a more natural feel. Transcatheter options let you avoid the big incision, and emerging technologies are shaping a future where valves could be lifelong, personalized, and maybe even gene‑powered.

What matters most is that you feel informed, empowered, and supported by a caring medical team. Ask questions, share your concerns, and remember that you’re not alone – many have walked this path and emerged with a healthier, happier heart.

If you’re ready to dive deeper, explore our detailed guides on heart valve testing, learn more about pediatric heart valve options, or read about the latest in child cardiac surgery. Your journey starts with knowledge, and we’re right here beside you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.